Adverse Childhood Experiences

How Does Shame From Toxic Childhood Stress Still Harm Us?

Hidden wounds from adverse childhood experiences may run in the background.

Posted October 18, 2021 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- Adverse childhood experiences shape psychological development, typically leading to shame.

- Because shame is imprinted in the right brain, it is usually experienced as a felt sense, rather than a conscious thought.

- Although shame usually goes underground, it exerts chronic harmful effects in adulthood.

- Shame can be effectively modified, but usually not through traditional talk therapies.

You’ve undoubtedly known adults who on the outside are bright, pleasant, attractive, and/or accomplished. Yet deep inside, they dislike themselves and no amount of persuasion can change the painfully negative way they experience themselves. Perhaps you’ve even felt that way. What’s going on? It seems to defy logic. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) provide a clue to this puzzle.

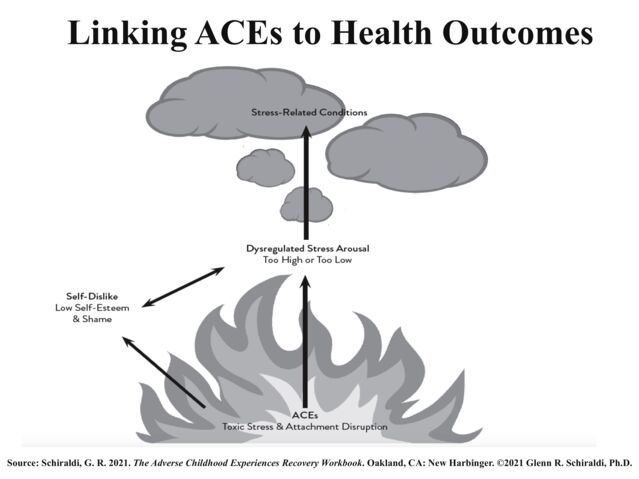

Recent blogs have explained how abuse, neglect, turmoil at home, or other ACEs in the first eighteen years of life are threat conditions. They signal danger to the developing child and often lead to dysregulated stress. Dysregulated stress, in turn, causes changes in the brain and body that influence the course of the many medical and psychological disorders that are predicted by ACEs, as shown below.

As the above diagram depicts, ACEs also shape psychological development in ways that commonly lead to shame, self-dislike, and low self-esteem. Shame is feeling bad to the core. It is experiencing the core self as damaged, defective, inadequate, or disgusting. It overlaps considerably with self-dislike and damaged self-esteem and amounts to self-loathing and self-contempt. (Note that damaged self-esteem is related to many psychological conditions, such as PTSD, depression, anxiety, addictions, alcohol abuse, and risky sexual behaviors.) Shame is painful; it typically exacerbates or maintains stress dysregulation.

Shame can be imprinted implicitly in the first months and years of life. The left brain stores and consciously recalls memories with words and logic. However, before the left brain sufficiently develops (by around the third year of life), the right brain stores memories of ACEs beneath conscious awareness.

What is imprinted is not a logical conclusion that can be described in words. It is more of a felt sense—a sense of “wrongness” that plays out in the body and emotions, not words and logic. Thus, it is usually difficult to talk or reason someone out of shameful feelings (a left-brain, cognitive approach) because the experience of shame is imprinted in the non-verbal right brain.

Shame is secretive, It goes underground, hiding in the shadows. We tend to block it from awareness because it is painful, but it continues to influence our present lives.

Shame in Later Childhood

By around age three, the left brain is sufficiently developed so that it can consciously process memories with words and reason. Thus, shaming experiences in the later years of childhood (such as verbal criticism or name-calling) can be stored in the left brain. In addition, overwhelming stress in the later years causes the left brain to go offline (to shut down; there’s no time to think or talk), while the right brain, with its deep connections to the survival and emotional regions of the brain, takes over. Either way, shaming memories can be imprinted afresh and can pile upon old shame memories. Shaming experiences in adulthood (such as a critical boss or rejection in love) can also trigger old implicitly embedded shame memories and stir up many non-verbal symptoms that can seem bewildering—until one realizes that it is childhood shame that is being triggered.

Basic Needs

Shame from the early years becomes locked in the brain’s wiring, playing out beneath the surface for years to come. Shame counters the basic needs to feel: unconditionally worthwhile as a person; loving and lovable; generally adequate; basically good (i.e., having good character); safe; and that one can overcome adversity and grow.

For example, a beautiful, academically accomplished high school student had been abandoned at birth by her father. She felt that she didn’t matter; that she was unlovable and worthless. She turned to drugs and sex in a futile attempt to kill her pain and feel accepted.

Growing up with a ruthlessly critical father who treated him like garbage, a successful accountant felt that he was garbage. He spent his adult life frenetically and joylessly trying to prove his worth through career achievements. His efforts didn’t work because they failed to address his deep hidden wounds. Feeling that he had to hide his imperfections from others kept him from letting people really get to know him. He began unethical business practices in an attempt to become even more “successful,” but his compromised integrity added to his shame.

Nora was a successful professional athlete who suffered from panic attacks and anxiety. Before games, she couldn’t sleep. Her gut tightened, she often felt nauseous, and she had bowel problems. She thought, “My life is great; I don’t know why I’m so anxious.” She never connected her present fears to the fear that was imprinted in her earliest years. Although she portrayed her parents as “normal,” they were stern, critical, and distant. She felt that their love and approval were conditioned upon accomplishments. She’d also internalized their criticism and became highly self-critical.

John always felt different, odd, like he didn’t fit in. He didn’t realize that this was shame. Naming it and accepting it was the first step to taking corrective action.

Hope for the Future

Shame is not usually responsive to talking and thinking. Healing comes more from the heart—acknowledging the pain, and healing and rewiring it with acceptance and compassion.

The diagram above suggests hope and intervention points to improve well-being. We can get to the root of suffering by settling disturbing memories of ACEs. We can regulate physical and emotional stress arousal. And, critically important, we can learn to neutralize shame and reverse low self-esteem.

Disturbing memories that are imprinted in the brain can be rewired. Learning to experience ourselves favorably and kindly is a skill that can be mastered, as we’ll discuss in future blogs.

References

Schiraldi, G. R. 2021). The Adverse Childhood Experiences Recovery Workbook. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger.