Positive Psychology

What Does It Mean to Have Passion and Purpose?

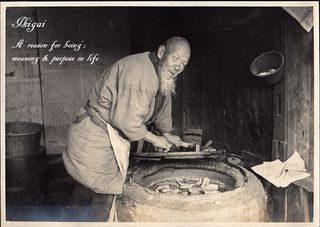

The Japanese notion of ikigai may hold the key

Posted April 3, 2018

If you regularly use social media, you may have seen an intriguing petal-like image pop up in your timeline. It features four overlapping circles, arranged in a cross formation like a complex Venn diagram: one at the top, one to the right, one at the bottom, and one to the left. These circles represent, respectively, ‘what you love’, ‘what the world needs’, ‘what you can be paid for’, and ‘what you are good at’. And their intersections signify: your mission (you love it, and it’s needed); your vocation (it’s needed, and pays); your profession (you’re paid, and good at it); and your passion (you’re good at it and love it).

Valuing what you do

Perhaps by now you are mentally assessing where your various life activities fit into this diagram. If you’re fortunate, you may indeed have a mission, vocation, profession or vocation. You might even feel that there is something that touches upon three circles. Which sounds pretty good. However, if it’s only three, there may yet be something missing.

Something you love, are good at, and the world needs may be wonderfully fulfilling. But if it doesn’t pay, it can be tricky to pursue long-term. Think of the struggling artist. If it does pay, but the world doesn’t need it, it could feel useless. Here David Graeber’s notion of ‘bullshit jobs’, designed simply to keep people busy, comes to mind. If you’re good at it, get paid, and the world needs it, you may feel secure and rewarded. But without love, it could feel empty. Falling into a career just because you excel at the relevant skills, or because you were pressured, might fall into that category. Finally, you might love it, get paid, and the world needs it. And yet without being good at it, you may harbour insecurities, as per the ‘imposter syndrome’.

Seeking ikigai

But what if you’re blessed enough to find something that includes all four circles? Then, according to the figure, you would have attained ikigai. This is explained as having a ‘reason to live’, a benevolent sense that life is ‘good and meaningful,’ that it is ‘worthwhile to continue living’1. But where does the term come from? And why do we find it gracing images like the one described above?

To answer the first question, ikigai is Japanese. It has come to attention through the work of people like longevity scholar Dan Buettner, with his work on so-called blue zones. These are places whose inhabitants enjoy healthier and longer lives than peers elsewhere. They include Sardinia (Italy), Nicoya Peninsula (Costa Rica), Icaria (Greece), Loma Linda (California), and Okinawa (Japan). And Buettner suggests that longevity in these places is due to a combination of factors, including a mostly vegetarian diet, moderate regular physical activity, and … ikigai.

For Buettner, ikigai is the sweet spot where your values align with what you like to do and are good at. This is roughly the same intersection as captured by the figure described above (minus the part about getting paid). Moreover, he contends that ikigai is common across all blue zones, even if the inhabitants do not have a specific word for it.

Embracing ikigai

As such, ikigai is a beautiful example of an ‘untranslatable’ word. These lack an exact equivalent in our own language, which is why – in the absence of a relevant native term – we often ‘borrow’ these and deploy them as loanwords, as with ikigai. For they allow us to identify and express phenomena which our own language struggles to accommodate.

For that reason, I’ve been searching for such words, focusing on wellbeing in particular (being a researcher in positive psychology). My aim is to create positive lexicography, as I explore in two new books (see bio for details).

As ikigai shows, such terms can be very useful. Of course, we already have conceptually-similar words, such as meaning, purpose, and fulfilment, together with research showing how important these are to wellbeing2. But these do not capture the great potential and significance of ikigai (otherwise these native terms would simply be used instead). Thus, as our lexicon expands to include such terms, so too does our understanding of life, and our ability to shape it for the better.

References

[1] Yamamoto-Mitani, N., & Wallhagen, M. (2002). Pursuit of psychological well-being (Ikigai) and the evolution of self-understanding in the context of caregiving in Japan. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 26(4), 399-417. p.399

[2] Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S., & Kaler, M. (2006). The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(1), 80-93.