Vagus Nerve

Fight-Flight-Freeze and Withdrawal

Part 1: Polyvagal theory and withdrawal as a secondary autonomic stress cycle.

Posted April 30, 2021 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- There is a third state of stress reaction that exists between fight, flight, and freeze: Withdrawal.

- Withdrawal is a predictable instinct to overwhelming encounters with danger and stress.

- In the short term, withdrawal is a helpful reaction that helps a survivor regroup and recuperate after trauma.

- In the long term, withdrawal becomes a prolonged and complex response that takes over and impedes trauma survivors' entire life.

Before Porges’ (2011) polyvagal theory became widely known, it was commonly thought that the autonomous nervous system has only two branches: the sympathetic system which manages in times of stress, and the parasympathetic which manages in calm.

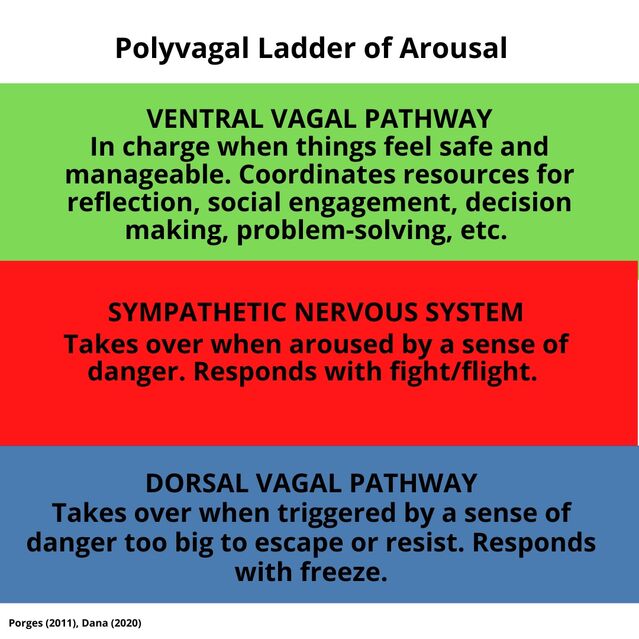

Porges’ polyvagal (PLV) theory posits that there are actually three branches, in a hierarchical relationship with each other. In simplest terms, the three pathways are:

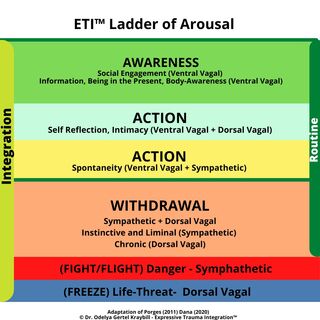

- The ventral vagal system, also known as the social nervous system, is in control when things feel safe. Part of the parasympathetic nervous system, it is the most recent in human evolutionary development and supports social engagement, thought, reflection, and awareness. These functions enable moral judgments and gain new learnings.

- The sympathetic nervous system provides a different system of reaction, the mobilization of fight and/or flight reactions. When the sympathetic nervous system takes over, the ventral vagal pathway shuts down.

- The dorsal vagal pathway forms a third system of response, the oldest and most primitive of the three. It activates in life-threatening situations, typically with a freeze response. When the dorsal vagal is in charge, the other two systems shut down.

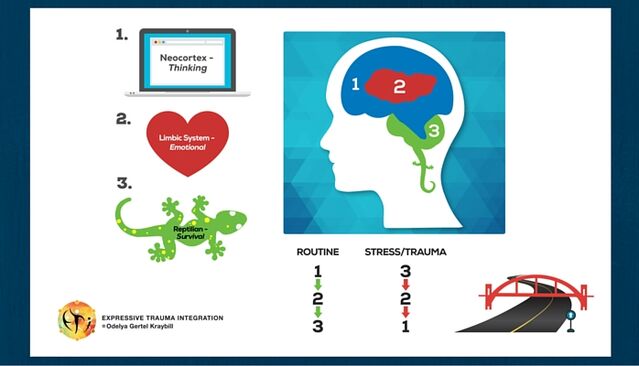

The concept of the triune brain (MacLean, 1985) is another earlier survival theory that divides the brain into three hierarchy systems. The two models have some similarities. In the language of the triune brain model, when we experience stress and/or life-threatening situations, we go into a 3-2-1* state. When we are safe and the upper parts of the brain are in charge (analogous to what polyvagal theory refers to as the social nervous system or ventral vagal) we are in a 1-2-3 state.

Both the triune model and PLV theory highlight states of extreme reactions to threat, namely fight-flight-or-freeze (3-2-1).

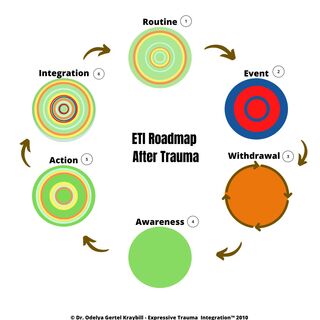

I propose an additional, mixed state that exists between fight/flight and freeze: withdrawal. Withdrawal is both a short-term reaction to immediate danger and a long-term reaction to overwhelming exposure to stress, danger, and life-threatening situations.

In reality, the trauma survivors who come and go, week in and week out in a clinical setting, dwell mostly in an in-between mode. They are exhaustingly hyper-alert, chronically anxious, often in an emotional freeze, but rarely in a full-blown state of shutdown or immobilization.

As a short-term reaction, we can understand withdrawal as a predictable instinct to overwhelming encounters with extreme danger. Universally, when the episode ends, survivors seek out a place of safety to recuperate physically and regroup emotionally.

For how long? It depends—on the depth of the trauma, the state of personal resources for coping, the level of safety in the environment, previous trauma history, and much more. Some people move on from withdrawal in a matter of days. Many require months, some require years. And some never return fully to the emotional presence they once displayed.

The struggle with long-term symptoms of withdrawal is what brings most survivors into therapy and a great deal of our work with them is about helping them learn to manage and live with withdrawal. This task looks different for each client. But we are dealing with reactions with deep biological rootings and the mechanisms involved are the same for everyone, regardless of gender, ethnicity, age, religion, etc.

In the essay in which I first encountered the concept in reference to conflict-resolution, Ron Kraybill (1988) described withdrawal as an instinctual and natural response to the pain of a particular relationship that sometimes becomes an obstacle between individuals after deep interpersonal conflict. That’s just one form of withdrawal.

In the context of trauma, for many survivors, withdrawal becomes a prolonged and complex response that takes over and impedes their entire life.

To work effectively with a chronic state of withdrawal, therapeutic responses must correspond to the complexity of the problem. We have to bring a systemic framework to treatment. In my next blog post, I’ll provide such a framework and show how to use it with survivors trapped in chronic withdrawal.

Click to read part 2.

References

Dana, D. (2020). Polyvagal Exercises for Safety and Connection: 50 Client-Centered Practices (Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology). WW Norton & Company.

Gertel Kraybill, O. (2010). Psychodrama and Trauma Integration Model. MA thesis. Lesley University. Natanya/Boston.

Kraybill, R. (1988). From head to heart: The cycle of reconciliation. Conciliation Quarterly, 7(4), 2-3.

MacLean, P. D. (1985). Brain evolution relating to family, play, and the separation call. Archives of general psychiatry, 42(4), 405-417.

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation (Norton Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology). WW Norton & Company.

Siegel, D. J. (1999). The developing mind: Toward a neurobiology of interpersonal experience. Guilford Press.