Eating Disorders

The Coexistence of Eating Disorders and Celiac Disease

An interacting and problematic relationship.

Posted July 1, 2021 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- The risk of developing anorexia nervosa after a diagnosis of celiac disease is doubled.

- The risk of celiac disease in patients with anorexia nervosa is higher compared to healthy adults.

- Eating disorders increase the likelihood of developing severe complications of celiac disease.

- The treatment should be adapted to help the patient adopt a gluten-free diet and address the eating-disorder psychopathology at the same time.

The first report describing the association between anorexia nervosa and celiac disease (or gluten intolerance) was published in 1966. Subsequently, other case reports on this association were reported in the early 2000s. However, only a 2017 longitudinal study on a large population of women found a positive and bidirectional association between celiac disease and anorexia nervosa.

The coexistence of the eating disorder with celiac disease, especially in forms characterized by being underweight and recurrent bingeing episodes, aggravates the clinical malabsorption and increases the likelihood of developing severe complications of celiac disease. On the other side of the coin, celiac disease can trigger and maintain the eating-disorder psychopathology in a subgroup of individuals upon the adoption of a diet that requires a total and permanent exclusion of foods containing gluten.

General information on celiac disease

Celiac disease is an inherited disorder caused by sensitivity to the gliadin fraction of gluten — a protein found in wheat, but similar proteins are present in rye, barley, Kamut, and triticale. Gluten-sensitive T cells are activated in a genetically susceptible individual when the antigenic determinant of gluten-derived peptides is presented. The inflammatory response determines the characteristic atrophy of the mucosal villi in the intestine and consequent malabsorption of nutrients.

Like all autoimmune diseases, celiac disease has multifactorial causes that include the complex interaction of genetic and environmental factors. While exposure to gluten is the triggering environmental factor, genetic determinants have not yet been fully elucidated. The disease is more frequent in females (1.5–2 times more common than in males) and populations of Indo-European origin. Patients with other diseases, such as lymphocytic colitis, Down’s syndrome, type 1 diabetes, and autoimmune thyroiditis (Hashimoto’s disease), are at greater risk of developing celiac disease.

Individuals with celiac disease usually report several gastrointestinal symptoms (diarrhea, steatorrhea, weight loss, bloating, flatulence, abdominal pain) and complications (abnormal liver function tests, iron deficiency anemia, vitamin D and calcium deficiency, bone diseases, herpetiform dermatitis, weight loss). Affected children present growth delay, apathy and generalized hypotony, abdominal distension, and muscle atrophy. However, some adult individuals do not report any symptoms.

Diagnosis of celiac disease should be performed by dose screening with serological markers (e.g., total A immunoglobulins [IgA] and IgA anti-transglutaminase tissue [tTG]) and confirmed in adults via biopsy of the second portion of the duodenum. Before testing for celiac disease, people who follow a normal diet should be advised to consume foods that contain gluten in more than one meal per day for at least six weeks.

The only treatment currently available for individuals with celiac disease is the total and permanent exclusion from the diet of gluten-containing foods, which involves avoiding foods containing wheat, rye, and barley. This treatment not only brings about rapid remission of symptoms associated with celiac disease (usually clinical healing occurs in about one to two months from the time of gluten exclusion) but also prevents the onset of serious complications (e.g., lymphoma, bowel cancer, and osteoporosis) which continuous and prolonged exposure to gluten causes in affected individuals. Ingestion of even small amounts of gluten-containing food hinders remission or causes a recurrence.

Two-way association between anorexia nervosa and celiac disease

A study carried out using the Swedish National Patient Registry, which assessed 17,959 women with celiac disease confirmed via duodenal biopsy and 89,379 women matched by age and sex, found a positive association between celiac disease and anorexia nervosa arising both before and after the diagnosis of celiac disease. Specifically, the study found that in women with celiac disease diagnosed before the age of 19, the odds of a previous diagnosis of anorexia nervosa were increased 4.5-fold after having paired the data by education level, socioeconomic status, and the presence of type 1 diabetes. In addition, those over 20 had an almost double risk of developing anorexia nervosa after an initial diagnosis of celiac disease.

A recent systematic review assessing 23 observational studies confirmed the high prevalence of eating disorders in patients with celiac disease (about 8.88 percent). Moreover, the study also found that the overall risk of celiac disease in patients with anorexia nervosa was 2.35 higher than in healthy adults. These two findings confirm the presence of a bidirectional association between celiac disease and eating disorders.

Mechanisms that explain the bidirectional association

There are at least two factors that could explain the presence of a bidirectional association between anorexia nervosa and celiac disease:

- Common genetic susceptibility. A recent genome-wide association study identified a significant genome-wide locus for anorexia nervosa on chromosome 12, in an area previously identified as being associated with type 1 diabetes and autoimmune diseases. This will hopefully prompt the study of the genetic relationship between anorexia nervosa and autoimmune gastrointestinal diseases.

- Surveillance bias. Individuals with anorexia nervosa and celiac disease are generally studied more carefully than the general population, leading to a more frequent diagnosis of the other condition.

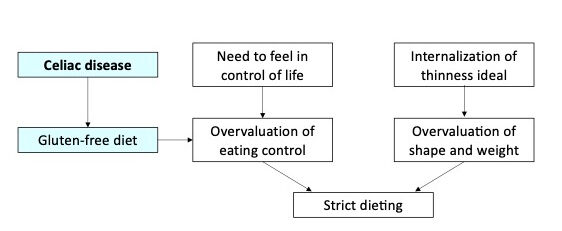

Although celiac disease has not yet been proven to be a risk factor for the development of eating disorders, it can be hypothesized that, in line with transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral theory, the presence of gastrointestinal symptoms and the need to follow a gluten-free diet may promote the onset of overvaluation of eating control and the adoption a strict diet (Figure 1)—one of the access routes to eating disorders—in individuals who need control in general.

Attention to the initial diagnosis

Differential diagnosis of celiac disease and eating disorders can be complex, as many signs and symptoms are present in both disorders (Table 1). Usually, patients present with some nonspecific abdominal symptoms (e.g., diarrhea, abdominal bloating, or pain), and the doctor’s task is to identify the cause of these symptoms to guide the therapeutic intervention.

The presence of asthenia and abdominal symptoms (particularly diarrhea and steatorrhea) and the absence of eating-disorder psychopathology (i.e., the overvaluation of shape, weight, eating, and their control) are two important indications of the culprit may be celiac disease. In this event, the first step is to prescribe the tests described above to assess for the presence of gluten intolerance. If these tests are positive, and in no other case, it is advisable to prescribe the patient a gluten-free diet. On the other hand, if tests for celiac disease are negative, and the patient reports the overvaluation of shape, weight, eating, and their control, often associated with a strong fear of gaining weight, the diagnosis of an eating disorder should be considered.

Table 1. Main signs and symptoms in common between celiac disease and anorexia nervosa include:

- Weight loss

- Short stature and/or thinness

- Osteopenia/osteoporosis

- Borborygmus

- Meteorism

- Abdominal distension

- Abdominal cramps

- Vomiting

- Regurgitation

- Epigastric pain

- Heartburn

- Asthenia

- Iron-deficiency anemia

- Folate and B12 deficiency anemia

Interaction between eating disorders and celiac disease

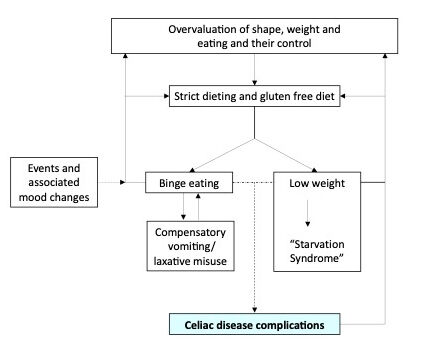

When they coexist, eating disorders and celiac disease interact negatively with each other through numerous mechanisms (Figure 2): (i) the gluten-free diet can promote an increase in eating concerns and consequently intensify dietary restriction and restraint, promoting weight loss (or hindering weight regain) and the onset of binge-eating episodes; (ii) binge-eating episodes, in which gluten-containing foods are usually ingested, keep celiac disease active; (iii) foods containing gluten may be ingested on purpose to promote weight loss; and (iv) malnutrition and osteoporosis caused by the low weight in eating disorders can be accentuated by the malabsorption produced by celiac disease.

Treatment

In some cases, the presence of celiac disease creates an obstacle to the psychological treatment of eating disorders. Indeed, adopting a gluten-free diet may maintain eating-disorder psychopathology, making it more difficult to address the high levels of dietary restraint and restriction that are key mechanisms reinforcing the eating-disorder psychopathology. For this reason, the treatment should be adapted to help the patient adopt a gluten-free diet and address weight regain (if indicated) at the same time.

Patients should be helped to follow healthy and "flexible" dietary guidelines, inevitably excluding gluten-containing foods. Because of the nutritional risks associated with celiac disease, a registered dietitian must be part of the eating disorder care team to monitor the patient’s nutritional status. Moreover, the patient should always be monitored by a doctor experienced in the assessment and management of malnutrition secondary to malabsorption and/or weight loss. In these cases, specific vitamin and mineral supplements may be prescribed to the patient to replenish the nutritional deficit.

References

Dalle Grave, R., Sartirana, M., & Calugi, S. (2021). Complex cases and comorbidity in eating disorders. Assessment and management. Springer Nature. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-69341-1

Nikniaz, Z., Beheshti, S., Abbasalizad Farhangi, M., & Nikniaz, L. (2021, May 27). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence and odds of eating disorders in patients with celiac disease and vice-versa. International Journal of Eating Disorders. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23561

Marild, K., Stordal, K., Bulik, C. M., Rewers, M., Ekbom, A., Liu, E., & Ludvigsson, J. F. (2017). Celiac Disease and Anorexia Nervosa: A Nationwide Study. Pediatrics, 139(5). doi:10.1542/peds.2016-4367

National Institute for Health and Care and Clinical Excellence. (September 2015). Coeliac disease: recognition, assessment and management | Guidance and guidelines | NICE. Retrieved from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng20