Psychoanalysis

From Disorder to Discovery

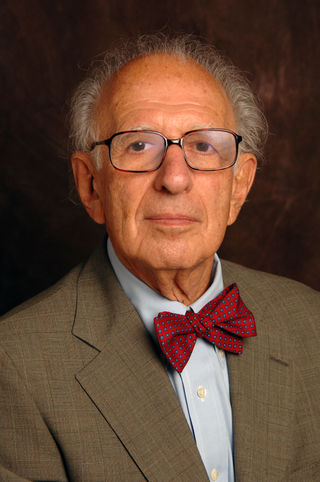

A conversation with neuroscientist and Nobel Laureate Eric Kandel.

Posted August 28, 2018

Neuroscientific breakthroughs often stem from the unfortunate yet revealing differences in thinking and behavior that appear when the brain doesn’t function normally. After nearly seven decades of research, neuroscientist and Nobel Laureate Eric Kandel’s new book, The Disordered Mind, catalogues the ways each type of brain disorder has allowed scientists to better understand our most complicated organ.

What motivated you to write this book, and why did you take the approach of exploring disorders to show how the healthy brain functions?

I’m trained as a psychiatrist and as a neurologist. In neurology, it’s routine to identify normal function by seeing patients with brain lesions that produce abnormality in that function. Subtle defects in specific brain regions can give rise to alterations in behavior that tell us something about ourselves.

Could you describe some of the disorders that have been most interesting to cover?

A major component of schizophrenia is actually an inability to make decisions. If you ask a schizophrenic patient “Will you come over for dinner?” He’ll say “no, it’s too much of a schlep” or “I don’t want to do it.” Once he gets to your house and sits down to dinner, he enjoys the meal as much as you and me, but the decision to make the journey is extremely hard for schizophrenic patients. One really learns from these disorders that they are extensions of normal processes that you and I take for granted, but that if it’s exaggerated in a particular fashion, it turns into a serious malfunction.

It’s also amazing how selective disorders can be. With Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease, you have a disorder of movement, but sensory information can be processed perfectly normally in most of those patients. It shows you the specificity of things in the brain. Even when disease is not pure to one system, you can still detect what the major theme of the illness is, and the major theme often correctly leads you to the neuroanatomical disorder.

This is why neurology has been such a powerful diagnostic discipline. When a patient died, people could see if they had a certain disease and where the lesion was. When larger brain areas are involved, it’s proven much more difficult to pinpoint specific diseases to specific single areas. Now we’re beginning to realize the combinations of areas implicated in specific diseases, but we don’t have a complete understanding of the areas involved in complex psychiatric disorders. That will be the next phase.

Once we have identified the regions involved, we can develop better treatments, because we can see with imaging technologies whether or not the drugs we’re giving to treat the illness even get to the region of the brain that’s involved.

Which brain disorders might we see significant progress on in the next five years?

We’re on the cusp of understanding schizophrenia better, and we’re on the cusp of understanding post-traumatic stress disorder better, which is a very common disorder. We’re beginning to see that there’s a genetic predisposition, so some are more sensitive to PTSD than others. We’re seeing that a number of specific regions are involved and not involved, and we’re beginning to develop agents that can counteract it. We’ve made a lot of progress.

We’ve also learned something very interesting, that I think some of the Army physicians have known for a long time. With PTSD, the sooner you treat, the better off the patient is. If you have physicians at the battle front who see a casualty within hours of the trauma occurring, they’re much more likely to be able to help them than if they see the patient a day or two later, and certainly a week or two later. One of the important treatment steps is the assurance that somebody is aware you have a problem and will help you. If you have a caring physician telling you “I’m with you—you’re going to be in shock for a little while, but I’m confident that we can get you better,” that’s extremely therapeutic. The acknowledgement itself is like a medicine.

For PTSD and other disorders, the ability to detect damage to the brain is infinitely greater now than it was 40 years ago, which is a relatively short time in the history of medicine.

You seem very optimistic about how far neuroscience has come. What is the biggest challenge facing the field now?

The biology of consciousness. We have very little understanding of it. We realize it’s not localized in just a single structure, but that it probably involves a number of different regions, and very importantly the prefrontal cortex. The biology of consciousness—which is what makes us who we are—is fascinating. And we’re just at the beginning of understanding it, so it’s a major area moving ahead.

For example, are there different areas involved in consciousness of oneself versus consciousness of others? You would have to find subpopulations, such as people who have a defective consciousness of self. Once a subpopulation like that has been identified, then it should not be too difficult to try to delineate the area or areas involved.

You discuss the relationship between psychoanalysis and studying the mind biologically, and the importance of gathering empirical data on psychoanalysis. How do you see the relationship between the two areas now?

Let me show you how much psychoanalysis has suffered because it was so slow in trying to identify what was going on in the brain. I’m trained as a psychiatrist, and I wanted to be a psychoanalyst. When I was getting out of my training at Harvard in the early 1960s, you couldn’t be chair of the psychiatry department if you were not a psychoanalyst. Now you can’t be a chairman if you are a psychoanalyst. Why? Because the analysts were so successful in 1950s and 1960s, that they never tried to study it. They never tried to see what it was that worked and what went on in the brain. They dealt with a set of psychological constructs: the ego, the id, and the superego. They didn’t deal with specific brain structures. For a while, this was so romantic, so new, and so daring, that it brought along the whole medical profession. But after a while, they wanted to see proof. Do an outcome study. Show that analytically oriented psychotherapy works better than this or that. When that research moved further along, weaknesses emerged in the psychoanalytic approach that weren’t even considered earlier. That led to a big disappointment in what could be accomplished. Now there’s a more balanced approach, but it’s been a long time coming.

Has studying the brain changed any aspects of your daily life?

The things I’ve learned have influenced me a lot. For example, I’m 89 years old. I’m not getting any younger, so I’m beginning to worry about age-related disorders, especially age-related memory disorder. I recently worked with a colleague who has been involved in showing that bone is an endocrine organ, and it releases a hormone called osteocalcin. I began to wonder whether it might contribute to age-related memory loss. I studied age-related memory loss in experimental animals, and I showed, indeed, when you give them more osteocalcin, you can reverse age-related memory loss. Moreover, if you got them to walk a lot, by putting them on a treadmill, you could reverse age-related memory loss. I used to swim almost every day. Now I’m switching from swimming to walking. I think the pounding of the bones is more likely to result in the release of osteocalcin. I’ve not shown this, but it’s something that I or others should test someday.

Your desire to understand the brain was driven by your experience growing up in Nazi-occupied Europe—you wanted to understand morality and the basis of evil. Do you feel that you’ve been able to address that question?

That’s a deep question that I must say I have not made a lot of progress on. It’s amazing how rather civilized people can, under demagogic leadership, be converted to demons. One really needs constant vigilance. As soon as one sees leadership with a tendency to be despotic, discriminating, or dangerous, one has to rally democratic forces within the state in order to combat that. Often that doesn’t happen in time, so horrible people take control of the government and move it in awful directions. The sociological and psychological factors are more immediately relevant, but these changes also have biological underpinnings. As we understand that more and more, we can make an even greater impact on these issues.

What is the most important piece of information you want readers to take away?

I think rather than a single fact, it’s an attitude. Understanding the brain is going to give us better insight into how to manage our lives, understand what’s happening to ourselves, to our loved ones, to our friends, to our enemies, and it gives us a better window into the human mind. It’s such a complex organ. And it affects us. No, it controls us. The more we understand it, the better off we are. I encourage people to do more work in this area, gain a deeper understanding, and so begin to really help us structure a society that is more functional, more democratic, and more decent than we had before.