Spirituality

How Healthy Spirituality and Religious Fundamentalism Differ

One requires spiritual battle with humanity, modernity, pluralism, and science.

Updated April 24, 2024 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- Leaders often exert control via the doctrine of total depravity, authoritarianism, and scriptural literalism.

- Healthy spirituality promotes a consensual, individualized spiritual journey and balances faith with reason.

Although corruption within religious institutions is common knowledge, rarely do we get around to discussing how religious abuse can overlap with the victim-blaming tactics of narcissistic abuse, the mob mentality of cults, the racialized mythologies framing eugenics rhetoric, and/or the (often militarized) suppression of mass media, secular higher education, Enlightenment values, and democratic political opposition by authoritarian regimes.

This particular convergence is the very essence of religious fundamentalism–a political-religious doctrine linked with adultism and child abuse, misogyny, right-wing authoritarianism, and xenophobic neo-fascism. Research also associates religious fundamentalism, across all faiths, with brain damage, low cognitive flexibility, gullibility to conspiracies/propaganda, both low self-esteem and narcissism, persecutory delusions, and unhealthy perfectionism.

In the U.S., religious fundamentalists are the single-largest—and most organized—voting bloc opposing movements for reproductive justice, racial justice, (pandemic-related) disability justice, LGBTQ+ rights, gun control, climate justice, and other social justice issues. Disturbingly, their ideological aggression mirrors religious fundamentalists around the globe—from the New York Times reports of Hindu extremists rallying for the extermination of Muslims in India to Sinhalese Buddhists and Muslims reportedly terrorizing Sri Lankan Tamils, as depicted in activist-designer-rapper M.I.A.’s documentary.

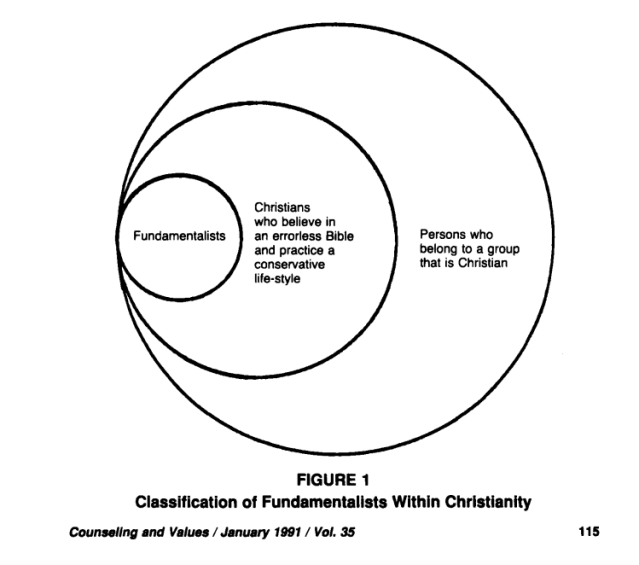

As mental health advocates who recognize the interconnectedness of all systemic injustices, it is imperative that we understand how religious fundamentalism threatens democracy. This public scholarship is intended to be used as a condensed primer that disassembles the ideology to 1) illustrate how and why it spans all religious doctrines and 2) how it differs from healthy spirituality, so that valid critiques of fundamentalism can pre-empt conflation with anti-theism. (Note: "G-d" is spelled as such out of respect for Jewish tradition regarding the utterance of divine names.)

The Basics: Fundamentalist Doctrine

Religious fundamentalism is a meta-belief that issues rigid edicts, often related to the sinfulness of all behaviors. The highest priority is often seen as surviving Judgment Day or its equivalent, not people’s welfare in the here and now.

Accordingly, in many cases, almost no degree of humanism or relationality factors into the rulebook. However, research shows that some people derive a sense of control and/or self-regulation from the ideology’s prescriptiveness.

My conceptual framework of religious fundamentalism includes seven pillars (to date):

- the belief that religious pluralism corrupts, and only one religion is/can be valid

- blaming society’s problems on secular modernization and younger generations

- ironclad in-group favoritism and a strict division between “us” and “them”

- apocalyptic anxiety and/or fantasies of rapture acceleration (e.g., excitement about climate destruction)

- mandatory evangelizing, with or without others’ consent

- constant “spiritual battle” with “The Enemy”

- authoritarian expectations of leaders (unquestioned dominion) and followers (total subordinance)

Some have argued that religious fundamentalism hardly focuses on G-d as much as it does exert power and control—intrapsychically, interpersonally, organizationally, and politically.

The Divergence: Fundamentalism vs. Healthy Spirituality

Arguably the most glaring differences between healthy spirituality and religious practice and religious fundamentalism emerge around authority, leadership, institutional power, and the censorship of knowledge.

First, fundamentalist leaders often instill self-doubt via the doctrine of total depravity. This standpoint frames humanity as innately depraved, wicked, and opposed to G-d’s will. Not only that, but it pits prayer and faith against self-help, initiative, and proactiveness. Redemption and continued submission to G-d’s will—often qualified by leaders—is the only way to transcend depravity.

Dismissing the possibility of innate human altruism, compounded with a disregard for actionable faith, only gives way to a false religion-activism dichotomy at the societal level. Moreover, the historical impact of many faith leaders—C.T. Vivian, James Lawson, James Cone, Joseph Lowery, Ralph Abernathy, activist-rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, and Gustavo Gutiérrez, father of liberation theology, to name a few—debunks the religion-activism binary.

The influence of this fundamentalist tenet is both personal and political. Whereas healthy spirituality can promote introspection and intuition, especially via mind-body awareness, fundamentalism indoctrinates emotional detachment by severing the mind and body. And, personally and politically, fundamentalism enables learned helplessness and spiritual bypassing. As a result, fundamentalist activism often champions negative rights versus positive rights.

Second, fundamentalist leaders often endorse authoritarianism. Marlene Winnell conceptualized Religious Trauma Syndrome (R.T.S.) to represent how a dictatorial leadership style and narcissistic abuse tactics can converge in fundamentalist clergy. Victims are often pathologized and scapegoated, while clergy successfully protect their image by playing the victim. R.T.S. overlaps with "Churches That Abuse," "25 Signs of Spiritual Abuse," and other models of religious abuse.

Whereas healthy spirituality promotes a consensual, individualized spiritual journey, religious fundamentalism mandates that authority unilaterally dictate and inspect all members’ spiritual awareness.

The authoritarian dynamic of fundamentalism, combined with the easily-roused guilt and gullibility of members, can allow leaders to weaponize shame and fear-mongering to deter autonomy and independent thinking.

Authoritarian logic can also justify the infliction of painful and humiliating punishments to which authorities would never consent. The outcome is undeterred reverence for leaders who destroy evidence of abuse and protect their reputations over people.

Lastly, fundamentalist leaders often promote scriptural literalism, a method of scriptural interpretation that adheres to the strictest connotation of word choice, disregarding figurative speech. Underlying this approach is a strong bias against secular accounts of history (e.g., archaeology) and the notion that sacred texts were supernaturally-manifested, not hand-written on scrolls by scribes, over the course of about 1,500 years. This position fuels both ahistoricism and superstitiousness, as pseudohistory can plant the seeds for conspiracy.

The film "1946: The Mistranslation that Shifted a Culture," for instance, exposes how the Revised Standard Version publishers’ committee replaced "malakoi" and "arsenokoitai"—Greek words for pervert–with "homosexual." And in 1983, Biblica, the copyright owner of the N.I.V. Bible, mistranslated German scripture. "Knabenschander"—connoting rampant pedophilia by Catholic priests±was replaced with "homosexual," just as the media deemed AIDS “the gay plague.”

So, when former President Trump’s Bible teacher attributed the origin of COVID-19 to gay men supposedly angering "G-d’s wrath," it came as no surprise to many. Nor was there much shock when televangelist Pat Robertson—Christian Broadcasting Network’s founder and The 700 Club’s host for 55 years—said on air that gay men shake hands wearing sharp rings to spread H.I.V purposely.

Whereas healthy spirituality aims to balance faith with reason, religious fundamentalism promotes anti-intellectualism, the over-spiritualizing of oppression and tragedy, and unquestioned acceptance of pseudohistory and pseudoscience. Considering this demographic’s high degree of gullibility to misinformation, political mobility, and strong moral incentive to reshape secular governments into theocratic regimes, the implications for the struggle to protect whatever degree of democracy we currently have are vast.