Health

Expressive Arts Therapy: The Original Psychotherapy

A true evolution inclusively acknowledges its history and origins.

Posted December 11, 2020 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

The Evolution of Psychotherapy conference is being held this week; it's the official meeting of the Milton H. Erikson Foundation. It is a widely attended program featuring select “master practitioners” in the field. For many professionals and students, it is sort of a “Woodstock” of mental health approaches and defines psychotherapy as “when Freud became interested in psychological aspects of medicine” (The Evolution of Psychotherapy, 2020). Many of those I call respected friends and colleagues are invited to present at this event.

I have attended this conference in the past, but not during the last 10 or more years. But I still look to it as sort of a signpost as to what the ruling psychotherapy "deciders" believe are the best practices and the leading voices. Yet despite the calls for diversity and emerging paradigms, the event has remained remarkably the same over the last decade, generally Eurocentric and dominated by white male voices.

I consider myself a psychotherapist by training and education. I am also a multi-decade practitioner of what is broadly known as expressive arts therapy or simply "expressive therapies" (Malchiodi, 2005). And I keep wondering when the psychotherapy “evolution” is going to realize exactly what voices are now blatantly missing from its gene pool.

The healing practices that form the foundation for contemporary expressive arts therapy as well as other forms of psychotherapy originally emerged and evolved in service of health and well-being over millennia and well before Freud appeared on the scene. Humans, in fact, historically have, and continue to use these practices and variations of them to reach psychological and physiological stability, including self- and co-regulation, self-exploration and understanding, and ultimately, restoration of self and community (Malchiodi, 2020).

So, I ask just where is what is the oldest form of restorative practice—expressive arts—in the mix? In a time period when cultural preferences for repair and restoration are being cited as essential to health and well-being, when exactly are the ruling voices of psychotherapy planning to recognize this part of its lineage?

And I am not talking about expressive approaches simply added to existing forms of talk therapy currently elevated to conference-worthy spotlight. I am referring to overdue recognition and inclusion of what are largely non-verbal forms of psychotherapeutic communication that have been applied for the past 50 years or more.

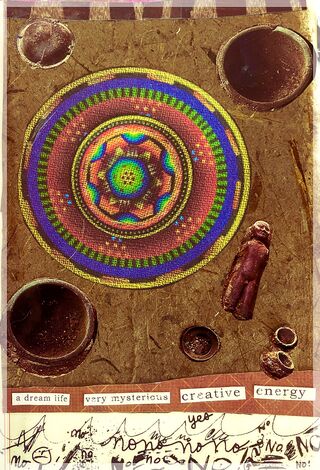

I am also advocating for psychotherapeutic practices that take place outside the traditional clinic, private practice office, or hospital, within communities and groups with shared experiences, values, and beliefs. These are methods and protocols not necessarily predicated on talk, but involve a variety of implicit and embodied procedures, ceremonies, routines, and rituals. They are expressive moments of synchrony, entrainment, interoception, sound, movement, enactment, and image. They are experiences that make central the value of social engagement, relationships, and communications that are solidified in ways beyond words alone.

So self-chosen deciders of what psychotherapy is, hear me out. The frameworks for expressive arts therapy are now clearly in view in the form of brain-wise models (Expressive Therapies Continuum) as well as through the lens of cultural anthropology and ethnology (see Expressive Arts Therapy is a Culturally Relevant Practice ). When we look at contemporary psychotherapeutic methods via the latter, storytelling (talk therapy) and somatically-resonant approaches (movement, gesture, enactment) are all derived from these historical as well as contemporary approaches. And within the currently exclusive narrative of contemporary psychotherapy is the lost thread of the indigenous contributions, practices that continue to be used throughout the world for restoration, health, and well-being. In order to become honest practitioners of healing methods, we must also come to terms with this exclusion as well.

There are two much larger topics for readers at this juncture, perhaps as points for future discussion. One is the notion that we psychotherapists must recognize that individuals, groups, and communities have the capacity and cultural mechanisms to access self-repair and restoration of the self. I certainly respect that talk therapy, as well as psychopharmacology, do change lives in significant and measurable ways. But we also know, again from thousands of years of human proclivity for self-expression, that non-verbal, embodied, and culturally-resonant practices form a significant piece of any transformation, meaning-making, and healing.

The second topic is one that I often muse about with my expressive arts psychotherapy colleagues. I speculate if there will come a time when mental health professionals will wonder why we were so intensely focused on talk as the cure for all that ails. Even the ultimate god-figure of the Evolution of Psychotherapy conference, Sigmund Freud (1920) said, “What the mind has forgotten, the body has not, thankfully.”

Communication is not exclusively language-based nor is it the only form of healing and transformation. For those of us engaging individuals, groups, and communities in the interoceptive and exteroceptive moments central to expressive communication, we already know this—that implicit, sensory-based experiences really are at the core of all repair, recovery, and restoration.

References

Freud, S. (1920). Beyond the pleasure principle. In J. Strachey (Ed.), Complete Psychological Works, Standard Ed. Vol 3. London, Hogarth Press, 1954.

Malchiodi, C. A. (2020). Trauma and expressive arts therapy: Brain, body, and imagination in the healing process. New York: Guilford Publications.

Malchiodi, C. A. (2005). Expressive therapies. New York: Guilford Publications.

The Evolution of Psychotherapy Conference. (2020). About The Evolution of Psychotherapy Conference. Retrieved on December 11, 2020 at https://www.evolutionofpsychotherapy.com/about.