Ethics and Morality

Sub-Human? The Psychology of Anthropocentric Exceptionalism

Emma Hakansson explains why it's not radical to fight human speciesism.

Posted July 19, 2024 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- Emma Hakansson's book clearly shows that other animals are not sub-human, simply different from human.

- Arguing against anthropocentric speciesism isn't radical but rather based in solid evolutionary biology.

- Humans are mammals, and when we act as if are separate from and above all other animals, oppression results.

- Animals should be free to express their dogness and hogness and not be demeaned for being who they are.

When I saw the title and then read Emma Håkansson’s new book Sub-Human: A 21st-Century Ethic; On Animals, Collective Liberation, and Us, I immediately wanted to know more about why she wrote it. Among the first things that came to mind is the fact that humans are mammals, and when we think everything revolves around us—that we’re exceptional and separate from and above all other animals—this is bad biology and results in unwarranted speciesism and oppression.1 We are exceptional in various ways, and so, too, are other animals.

The words we use to refer to humans and other animals deeply matter, and it’s clear that other animals are nonhumans, not subhumans. Humancentric hierarchies are totally misleading, and thinking about “higher” animals and “lower” animals makes no sense. This is not a radical view; it is solid evolutionary biology.

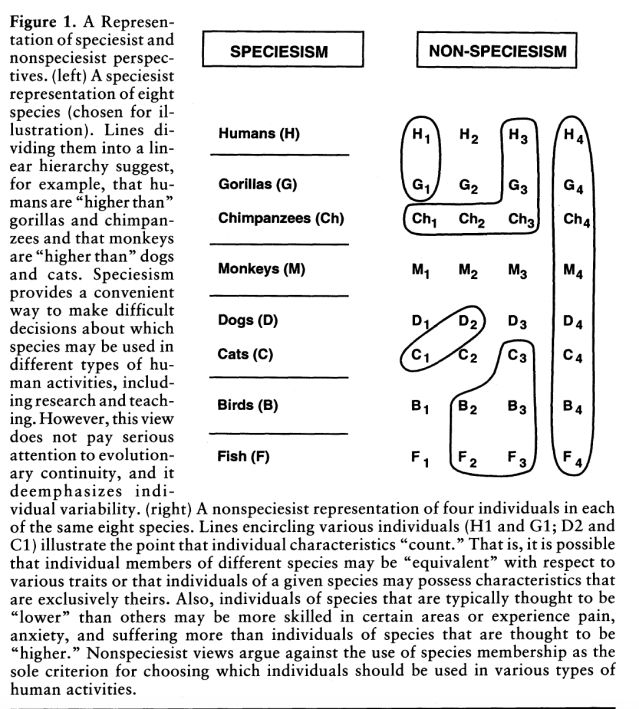

Simply put, anthropocentric speciesism doesn’t work, and other animals aren’t less than humans (Fig. 1). As Emma reminds us, “When we accept oppression of some, we feed the oppression of others, and we make space for domination driven by false ideas of inferiority and lesser worth. When we discount the inherent preciousness of animals who think and feel, we erase precious parts of ourselves.”

I’m pleased Emma could answer a few questions about Sub-Human in which she delves into what it means to be an animal, how our view of other animals impacts our view of other people, oppressions, and the planet, how we got here, as well as how we can move forward together. Her book is very timely as we move through an epoch called the Anthropocene, often called “the age of humanity.” In practice, the Anthropocene has morphed into “the rage of inhumanity.” We need to expand our self-centered mindsets and the community of equals.

Why did you write Sub-Human?

I wrote Sub-Human to invite those engaged in different social justice issues to consider how speciesism is a form of discrimination and oppression interlinked with others. If we were all better aware of the history of animal exploitation and efforts to move past it, we would also see how oppressions based on species, gender, race, and other arbitrary markers have perpetuated each other and, at their core, are the same. With this understanding, we can better work towards collective liberation—and Sub-Human traces this interwoven history and the potential path forward for justice.

How does your book relate to your background and general areas of interest?

I first became engaged in activism and theory for social justice through animal rights. As I began to extend my circle of compassion to include our fellow animals, their oppression and my growing understanding of it helped to connect other social justice issues in my mind.

For example, from a personal perspective, I understand my experience of child sexual abuse through a lens of child disempowerment, denial of child rights, and a disregard for the autonomy and mental and bodily safety of others by perpetrators of abuse. I am very interested in finding shared harms across social issue—feminism, racism, classism, and speciesism, for example—as I believe that in doing so we get closer to addressing the root cause of all of these.

Who do you hope to reach in your interesting and important book?

I hope those committed to dismantling some kinds of oppression but who have yet to consider the rights of animals will reconsider the issue and extend their view of who is deserving of justice to all species.

What are some of the major topics you consider?

In the book, I explore how we came to justify mass animal exploitation, slaughter, and oppression—from Descartes’ claim that other animals were mere flesh automatons to the denial of animal sentience by much more recent figures. I examine how this has led to industrialized and normalized violence against billions of individuals and how we might work to undo this immense harm by considering animal rights differently. So often, animal rights are viewed as distinct and outside of regular discussions of social justice, and I want that to change.

How does your book differ from others that are concerned with some of the same general topics?

Sub-Human brings together research and theory that I’ve not yet seen combined to paint such a fulsome picture of both the problem of speciesism and broader oppression and potential solutions for it. An interview with Dr. Melanie Joy helps to unpack the psychological justification behind speciesism, interviews with activists and lawyers explore how people have worked to change the system that permits violence against animals, and experts in environmental and ethical fields bring a holistic lens to how we view animal rights—an issue connected to environmental destruction and human rights violations, too. It’s a round-up of a lot of important existing thinking and an evolution of that thinking.

Are you hopeful that as people learn more about the mindset and ubiquity of oppression, they will pay more attention to how they interact with humans and other animals?

Definitely. So much of our oppression of our fellow animals is not conscious but inherited as we grow, learn, and develop within a deeply speciesist society. In the book, I share the story of how I first considered how language objectifies and oppresses animals when I referred to a chicken, even as I already considered myself as an animal rights advocate, as an “it,” as an object.

We so intensely internalize the commodification of other sentient beings, even if I think our human nature is to coexist with them. I hope the book might help people unpack and relearn some of what they have learned.

References

In conversation with Emma Håkansson, founding director of Collective Fashion Justice and author of Total Ethics fashion.

1) "Speciesism is the assumption of human superiority leading to the exploitation of non-human persons. It is a human-held belief that all other animal species are inferior to us. Speciesist thinking involves considering animals—who have their own desires, needs, and complex lives—as means to human ends. This supremacist line of “reasoning” is used to defend treating other living, feeling beings as property, sources of entertainment, objects to experiment on, wear, or even recipe ingredients. It’s a bias rooted in denying others their own agency, interests, and self-worth, often for personal gain."

Bekoff, M. Resisting speciesism and expanding the community of equals. BioScience. 48, 638-641, 1998.

_____. Deep Ethology, Animal Rights, and the Great Ape/Animal Project: Resisting Speciesism and Expanding the Community of Equals. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics. 1997, 10, 269-296.

The Psychology Behind Why We Love and Exploit Animals; Individual Animals Count: Speciesism Doesn't Work; Anthropocene Psychology: Dogs as Mirrors of Human Behavior; "Hidden": Animals Struggling to Coexist in the Anthropocene; Anthrozoology: Embracing Co-existence in the Anthropocene; The Psychology of "Saving the World" in the Anthropocene; Assuming Chickens Suffer Less Than Pigs Is Idle Speciesism; Individual Animals Count: Speciesism Doesn't Work; Rewilding 2023 Demands Expanding Our Self-Centered Mindsets; Animal Minds and the Foible of Human Exceptionalism.