Animal Behavior

Dogs Demystified: A Delightful Guide to All Things Canine

A must-read for fluency in “dog” and for bettering the dog-human relationship.

Posted May 31, 2023 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

- Ethologist Marc Bekoff’s newest book helps readers become fluent in “dog.”

- We can demystify our canine companions by understanding how they sense their world.

- Getting inside their furry minds and bodies can help us provide better care for our dogs.

My new favorite book, Dogs Demystified, is written by one of the world’s foremost authorities on dog behavior, Marc Bekoff, Ph.D. (He also happens to be my favorite dog expert.)

I had an email conversation with Bekoff and asked him to answer a few questions.

What would you like readers to know about the book?

Dogs Demystified largely focuses on dog behavior—what dogs do and how and why they do it—to help readers see, appreciate, and respect dogs for who they are and not what we want them to be. A large part of demystifying our canine companions is understanding how they sense their world, and I hope this guide helps you get eye-to-eye, nose-to-nose, and ear-to-ear with dogs. Getting a good handle on what is happening inside a dog’s head and heart is how we can minimize the border between them and us. When we can do that, we are better able to help dogs be dogs—to do what comes naturally—in a world where many aspects of their lives are often controlled and compromised by humans.

As a cognitive ethologist—a scientist who studies the inner lives of all sorts of nonhuman beings, including dogs—I want to introduce readers to animal research itself. In a conversational, nontechnical way, entries explain research terms and how science is conducted. I also dispel nagging myths such as dogs are our best friends and they are unconditional lovers, they are not. But they do form dominance hierarchies, and there are alpha dogs. I also stress there is no universal dog and we must be very careful about making statements such as “Dogs do this.” Or, “Dogs don’t do that.”

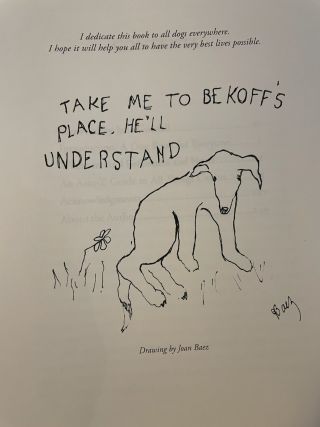

Also, singer and artist, Joan Baez, contributed four original drawings, and Paul McCartney wrote a story about a dog he and his family rescued.

What was the most interesting thing you learned about dogs that you hadn’t known?

In all honesty, while I do know a lot about dogs, my learning curve was vertical when I dove into the nitty-gritty of some of the scientific studies and tried to figure out why there was some disagreement among them. For example, researchers disagree about how dogs and wolves are similar and how they differ with respect to following human gazing and pointing. The bottom line here is not that some of the studies are bad but rather the differences emerge because different dogs are being studied in different labs with different researchers using different protocols. An important message: While we know a lot about dogs, there is a lot we don’t know and we should be careful about making sweeping statements about what dogs can and cannot do. I also included numerous stories from “citizen scientists” who really want to learn more about dogs and their wild relatives.

Are there any entries that you think will be especially controversial?

Some people might find my discussions about dominance, alphas, and theory of mind to be controversial. Detailed scientific research clearly shows that dogs do form dominance hierarchies just like their wild relatives, there are alpha dogs, and there is solid evidence that dogs most likely have a theory of mind, when they play, for example. We need to move away from the prejudice of thinking great apes are the only show in town when it comes to having a theory of mind.

What do you most want readers to take away from this book?

Great question. I hope they learn a lot, as I did; I hope they realize that there still is a lot to learn about dogs. It’s also important for readers to realize that around 75-80 percent of the estimated billion dogs who live on earth are free-ranging or feral. We need to study these latter populations to get a better handle on the cognitive, emotional, and moral lives of dogs because studying “homed” dogs in controlled laboratory setups tell only part of the story. This is not to say the lab studies are “bad,” but rather they have their limitations.

And giving dogs as many freedoms as possible—giving them lots of choices and agency—and getting their consent before we ask them or make them do something, are essential for having a solid two-way enduring relationship.

My deeper hope is that increased understanding will foster more caring. A dog’s feelings matter to them, and they should also matter to us. We should take the perspective and emotions of dogs into account in every aspect of our shared lives. This applies to training. I prefer to think of training as teaching and educating dogs about how to live in our human-oriented world—which should be done using only positive, force-free methods.

In reality, dogs are always learning from humans. We often place unrealistic social expectations on dogs, especially homed dogs, who are constantly being asked to do what we want them to do. Giving dogs some extra tender loving care is really good for them and for us. You can’t “spoil” a dog, nor are there really many bad dogs. Most of the time, when dogs misbehave, they’re simply doing whatever they have to do to be dogs. Training is a form of education; it’s not a way to program dogs so they always please us.

Dogs have rich and deep emotional lives, and we must honor and respect this bona fide scientific fact whenever we interact with them. Treating dogs as if they don’t have emotions is antiscientific; it damages the relationships dogs form with us and other dogs.

I agree with renowned singer and songwriter Emmylou Harris who told me, “Dogs are a sacred responsibility, dogs make us better humans, and dogs are one of the universe’s best gifts.” When people embrace these ideas, the world will be better for dogs and people.