Suicide

Ajax and the Lethality of Shame

On shame and suicide.

Updated November 1, 2023 Reviewed by Monica Vilhauer

Key points

- Shame is a significant, often unappreciated risk factor for suicide.

- The neurobiology of shame is related to the neurobiology of pain.

- Shame is an evolutionarily conserved aspect of group cohesion.

In Sophocles’ play, the Greek warrior Ajax insults the goddess Athena. It is never a good idea to insult a goddess — especially one who is the daughter of Zeus. In revenge, Athena casts a spell on Ajax causing him to imagine that a flock of sheep is a battalion of warriors. He slays every one of the sheep.

On realizing what he has done, Ajax falls into a state of unrelenting despair. He curses his behavior. He curses himself. He curses his life. “I do not belong,” he curses into the night.

On hearing of these events, instructions are given that Ajax not be left alone. These instructions are not followed. Ajax obtains a sword, plants it in the earth, and impales himself. He bleeds to death.

Sophocles was aware of the dangers of shame. He was aware that shame fills its victim with pain and remorse. He was aware that, like a cancer, shame is unrelenting. He was aware that “I do not belong,” is the cry of someone in shame.

Why is shame so acute? Why is suicide often seen as the only escape? Why is shame so painful?

There are two places in the brain which register pain.

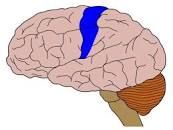

The sharp pain of a cut is carried on fast, large diameter fibers that transmit sensation to the spinal cord, to the thalamus, and finally to the postcentral gyrus of the parietal cortex.

And when this sensation reaches the parietal lobe — "Ow! That hurts!" — pain is felt.

In addition to the sensations carried by these fast, large diameter fibers, pain is also carried by slow, small diameter fibers. These fibers ascend the spinal cord and instead of going to the postcentral gyrus of the parietal lobe where acute pain is registered, these impulses are directed to a more primitive part of the brain. This pain is not experienced as the acute pain of a cut. Rather, it is experienced as the slow, insinuating pain of a wound that will not heal, a wound which saps energy, sleep, strength, hope. This is the pain of decay. This is "sickness pain," which is registered in the cingulate cortex, a more primitive part of the brain which is common to reptiles as well as to mammals, to non-human primates, and to man.

Unlike reptiles, which do fine on their own, a mammal’s place in the group is vital to its survival.

When an immature wolf, lion, zebra, or baboon is confronted by the alpha of its pack, the young mammal is faced with an urgent task. It must communicate that it has no intention of challenging the alpha. If the young animal fails, it will be attacked and probably killed or forced to leave the pack — a path likely leading to premature death. But if the animal can communicate acceptance and submission, then attack is averted, and the animal’s place in the pack is preserved.

How does the young animal decide what to do?

It doesn’t. The behavior is an instinct.

When a mammal's place in the group is threatened, there is input to the same cingulate cortex — the same part of the brain which registers sickness pain, and the same part of the brain we share with reptiles. This communication mobilizes primitive responses leading to changes in the physiologic status, with a fall in core neurotransmitters and a heightened parasympathetic tone leading to “freeze-dissociate” behavior — the other side of "fight-flight”.

The young mammal cowers, lowers its eyes and ears, retracts its teeth, and exposes its neck. It's heart rate slows. It's breathing almost comes to a stop. All this is done to appear as small and vulnerable as possible, reflecting an instinctive, biologic response of submission. An animal does not choose this behavior any more than an animal chooses to increase its heart rate after an acute loss of blood.

This same area of the brain — the cingulate cortex — that organizes sickness pain and submission in mammals and non-human primates also organizes our experience of shame.

Shame is primitive and biologic.

Shame is evolutionarily preserved.

Shame is evolved from pain.

Shame is an expression of the sense of unworthiness.

Shame is an expression of the unworthiness to live.

“I do not belong,” is an expression of shame. “I do not belong,” is why someone in a state of shame should not be left alone.

If you or someone you love is contemplating suicide, seek help immediately. For help 24/7 dial 988 for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, or reach out to the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741741. To find a therapist near you, visit the Psychology Today Therapy Directory.