Toward Greater Intimacy

Long-term relationships are hard, especially when it comes to sustaining passion. But novel ways of thinking about sexual satisfaction and understanding each other's needs can help partners whose sex lives fall short of their ideals.

By Psychology Today Contributors published July 6, 2021 - last reviewed on July 6, 2021

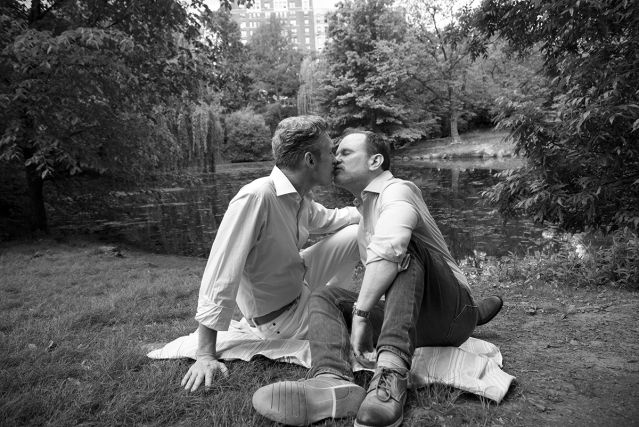

Bill O’Donnell & Kristian Kraai

“I can be very self-centered, but somehow I’m able to stop and remember what a partnership we have, how much Kristian does for me and invests in our relationship, and how much faith he has in us. It helps me zoom back and see the big picture rather than the passing storms of my own moods,” says Bill O’Donnell of New York City, referring to his husband, Kristian Kraai, left. The couple has been together since 1989 and married since 2016.“I can’t ever imagine not being there to take care of him," Bill says. Kristian agrees: "He is so easy to love."

The Purpose of Passion

Stop blaming yourself or your partner if your sex life is not what you desire. There’s a reason for it, and for many, work-arounds are possible.

By Marianne Brandon, Ph.D.

Sometimes, when a couple begins having less frequent sex, the man may think his partner’s libido is low, but that may not be the case; it may just be that she doesn’t want to have sex with him anymore. He tries to be understanding of her work and family pressures and distractions, but the source of her stress may be sex itself: It can be a horrible feeling to want sex, but not to want it with your partner.

Often, it’s not about love; these partners may love each other without question. If only they could have sex, their relationship would be almost perfect. But no one can tell the body what to want. In some cases, this leads to infidelity—even if the problem is not caused by a partner’s desire for someone else, people may seek an attractive alternative if they begin to feel a void their partner cannot fill.

Most people in this predicament do not desire a celibate life, but they may not seek a divorce, affair, or open marriage, either. They feel stuck, guilty, sad, ashamed, and confused, because they honestly don’t know how it happened: They loved sex with their partner, for years or even decades. And then something changed.

Now What?

A lack of passion may not be personal but a challenge presented by evolutionary design. As I see it, your body wasn’t designed to stay in lust with the same person for years on end. The evolutionary purpose of passion isn’t to keep a couple together for decades but to motivate short-term pair bonding and procreation.

After that goal is achieved, our innate desire for a well-known partner may become more fragile; it may even subside. Nonetheless, our sexual wiring remains intact, as is often discovered by those who find passion in the arms of an affair partner or re-enter the dating scene after a divorce. For those who want to stay together, though, there are options. Consciously accessing your primal, passionate selves, including playing with elements of dominance and vulnerability, could retrigger your desire. Seeing a therapist for guidance can also be helpful. Above all, rather than blaming yourself or your partner, consider the possibility that what’s happening is no one’s fault; nature will always be a powerful unconscious force in a couple’s love life. Sharing an intimate relationship with one partner over time is a core challenge of being human. Hold yourself, and your partner, with love as you forge your intimate path together.

Marianne Brandon, Ph.D., is a clinical psychologist and the author of Monogamy: The Untold Story.

Viorica Stan & Hugh Morris

Husband-and-wife visual artists Hugh Morris and Viorica Stan live together in New York City and share a studio in Saugerties, NY. “We don’t always agree, but we fundamentally respect each other, enjoy each other’s company, and love each other,” he says. “I think there are equal parts determination and happenstance in any long-term relationship. Crises will happen, but the determination to stay together is paramount. You hope that your partner has the same determination at the same moment in time when the inevitable crisis occurs—but that is pure chance."

The Pleasures of Achieving a Flow State

New research sheds light on a novel way to boost sexual satisfaction and treat low desire.

By Emily Jamea, Ph.D.

Flow is a word we usually associate with extreme sports or artistic experiences. But my recent study, published in the Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, found that flow is a state enjoyed by people during sex as well. This was the first study to examine the relationship between flow and sexual satisfaction. We surveyed people in long-term, monogamous relationships and discovered that passionate, fulfilling sex is very much a possibility for older, married couples. Our study not only suggests that sex can improve with time but also that it may be one of the peak experiences couples share.

A lot of couples long for the passionate, seemingly effortless sex they see in the movies. While I remind them that what they are seeing are paid actors following a script, I understand what they mean, and as I contemplated it more, it occurred to me that what they may really be after is a flow state.

Why Flow Matters

Flow is a term coined by psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, who proposed eight characteristics of the experience: complete concentration, clarity of goals, transformation of time, intrinsic reward, effortlessness, balance of challenge and skills, merger of action and awareness, and feeling of control over the task. You may have heard surfers describe “being at one with the wave.” Or perhaps you’ve witnessed a group of musicians jam on their instruments, creating melodies that aren’t planned. Individuals who engage in activities that produce a flow state tend to report having more meaningful lives, experiencing greater overall well-being, and tending to feel happier than other people.

Since sex is an activity most adults engage in regularly, we wondered if by examining the relationship between flow and sexual satisfaction, we might find a new way of helping people access this meaningful state and conceptualizing the treatment of low desire.

Optimal Sexual Experiences

Canadian psychologist Peggy Kleinplatz and her team began studying optimal sexual experiences over a decade ago. Through a series of interviews, her team identified eight components of optimal sex, and the language her participants used appeared very similar to that used by people who experience flow. Previous participants in my own research have used similar language to describe their best sexual experiences—“It’s as if the rest of the world disappears,” for example, or “Time seems to stand still.” Therefore, it made sense to me to study the relationship between flow and sexual satisfaction using quantitative measures to see how our findings would compare to what others discovered qualitatively.

Our team sampled 100 participants in monogamous relationships to find out if it was possible for them to experience a state of flow during sex, and if so, whether this predicted sexual satisfaction. We were particularly interested in studying couples in long-term relationships because we hoped to debunk stereotypes that good sex happens only in the “honeymoon phase” or is reserved for the young and able-bodied.

Our participants completed an online survey consisting of two questionnaires—the New Sexual Satisfaction Scale and the Core Dispositional Flow State Scale. We found that flow was, in fact, a statistically significant positive predictor of both partner-focused and personal sexual satisfaction, and we did not find any significant gender differences in our results.

What makes this research exciting is that it gives us a new way of conceptualizing great sex and treating low desire. I am already finding that by teaching my clients how to induce a flow state, I can help them begin to transform their sex lives.

Emily Jamea, Ph.D., LMFT, LPC, is a certified sex therapist.

Jonell & Dennis Copeland

“We love to travel,” says Jonell Copeland, who lives in Ringoes, NJ, with her husband, Dennis. “He is our big-picture thinker, while I’m the detail planner. I schedule our trips down to the hour on a spreadsheet, and he makes sure that we’re getting what we need out of the experience.” She adds, “We’ve also recently become a bit obsessed with backgammon. It has really helped us enjoy each other’s company in a new way. We take the board with us everywhere and pull it out whenever there is enough time and space to play. But no matter who prevails, we end up doubled-over laughing."

What Men Want, and Why They Need It

Almost all men want to be sexually desired, but few actually feel that they are.

By Grant H. Brenner, M.D.

There’s no doubt that a caricatured version of male sexual desire dominates the culture, and that more nuanced views remain underrepresented, communicating that men must always be the initiator, never the object, of desire. Unchallenged, this characterization becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Men may feel pressure to act one way, and even exploring other approaches can bring them stigma and shame.

Men’s Need to Be Desired

Researchers Sarah Hunter Murray and Lori Brotto conducted structured interviews with 300 heterosexual men between the ages of 18 and 65 who were in a relationship. Participants responded to questions including: “How important is it to have your female partner desire you?” “How do you feel sexually desired by your partner?” and “What, if anything, do you wish your female partner was doing more of that would help you feel desired?”

All of the respondents said that feeling sexually desired was important to them; nearly 95 percent said it was very important. A few reported that in the absence of being desired, they would not be able to have sex at all due to lack of arousal or the impact on their self-esteem. And about 12 percent said they no longer felt desired in their relationship at all.

Ways of being desired were also significant. About 40 percent of the men said that verbal expressions of desire, such as being complimented or being engaged in sexual talk, were important. Some men felt more desired and aroused when a partner told them what she needed. Flirtation, including a sultry look or meaningful glance, was also important, as was nonsexual, romantic touch, such as a rub of the arm, a snuggle, or a quick kiss. Such touch, the men reported, made them feel not just desirable but special—and wanted not only for sex.

Lust as Common Ground

In the end, only 12 percent of men felt that they were truly desired. The rest hoped their partners would do more—be more dominant, romantic, flirtatious, or sexually interested. Feeling that they always had to be the ones to initiate sex, they reported, could be fatiguing and even boring. They wanted a more collaborative, active partner.

The truth may be that men and women are more alike than previously acknowledged. Recognizing this, while still valuing differences, could lay a foundation for more informed, nuanced, and effective communication, as well as sexual satisfaction.

Grant H. Brenner, M.D., is a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst and a co-author of Relationship Sanity and Irrelationship.

RK Beale & Evin Brinker

“Communication is everything to me,” says RK Beale, left, of Brooklyn, NY, whose partner, Evin Brinker, lives in Harlem. “I push Evin to talk even when she may not feel like it, but this is what helps me believe that I am being supported and heard. So after weeks of my talking her ear off, Evin suggested we start Self-Care Sundays to grow our intimacy.” Evin elaborates, “We alternate planning Sunday dates for each other that help us connect and relax. It could be as simple as watching movies from our secret list or as lavish as doing clay face masks and manicures in our matching robes."

Avoiding Infidelity

The conversation that could keep people from cheating.

By David Ludden, Ph.D.

Long-term sexual relationships are typically presumed to be monogamous. You expect your partner to be faithful, and your partner likely feels the same way about you. However, statistics suggest that infidelity occurs in as many as a quarter of all marriages. That fact presents a big question for relationship researchers: What predicts when a partner will cheat?

In the 1980s, psychologist Caryl Rusbult developed the investment model to explain commitment in relationships. According to this model, commitment depends on three factors: the quality of the relationship, shared investments (like property, children, and social status), and the quality and availability of attractive alternatives.

Further research explored whether a partner’s sociosexual orientation—generally, being more open to the idea of casual sex—predicted infidelity intention. And it did, to an extent. People who’d engaged in sociosexual behavior, which of course would include acts of infidelity, and those experiencing sociosexual desire, such as regular fantasies about being with other partners, were more inclined to stray. But simply being more comfortable with the idea of casual sex did not correspond with a greater intention to cheat. In fact, in this research, some people had a relatively high inclination to cheat even though they were not especially comfortable with casual sex. This speaks to our powerful need for sexual connection with another person and reminds us that some are willing to disregard their religious and moral beliefs when their sexual needs have been thwarted for too long. We may, it turns out, adjust our preference for short-term or long-term sexual relationships depending on our recent experience: Some who played the field in their youth can settle into happy monogamy, and some who are dissatisfied with their relationship can find ways to justify cheating desires or actions.

Beating Them to the Punch

Research by University of Toronto psychologist Yoobin Park and her colleague Sun W. Park highlights another potentially crucial consideration. We enter into relationships to satisfy our needs for connection, sexual intimacy, and companionship—but we also need to protect ourselves from being taken advantage of. When couples fall into patterns in which one does most of the giving and the other most of the taking, one may perceive that the other has become less committed, which often includes putting sex on the back burner. An uncommitted partner, most of us would conclude, is unlikely to meet our needs in the future and might even be thinking of leaving. Under these circumstances, it seems only prudent to be on the lookout for a potential alternative.

Park and Park tested this hypothesis in a study recently published in the journal Current Psychology. Their team asked 289 married adults, most of them in their 30s, to complete an online measure of their own level of commitment to their relationship, as well as their partner’s. In this way, participants revealed their perceived partner commitment—how committed they believed their spouse was to them. They also responded to statements that assessed how much attention they paid to attractive people around them.

Perceptions, of course, do not always reflect reality. Just because we believe a partner isn’t highly committed doesn’t mean it’s true. Nevertheless, our behavior is guided by our perceptions because they form the only version of reality we know. But in this study, when researchers compared answers from both partners, they found the correlations between their perceptions to be fairly strong: They knew each other well.

The results supported the hypothesis that people are more likely to consider other relationship options when they believe their spouse is no longer committed to their marriage. And the person’s own level of commitment was not a good indicator of infidelity intentions: Even when participants said they wanted their marriage to last, they would still look around for other relationship options if they believed their partner was no longer committed.

This study highlights the importance of looking beyond the individual to the larger context when trying to understand motivations for infidelity. The researchers identified people who were considering cheating (or had already done so) not because they lost commitment to their marriage but because they believed their partner no longer cared about them.

Counselors will serve couples better by helping them recognize all of the factors that lead to a breach of trust. The idea is not to absolve a cheating partner from responsibility or to shift blame to the spouse who was cheated on. But all parties need to understand that infidelity isn’t just a matter of weak morals. Circumstance matters. n

David Ludden, Ph.D., is a professor of psychology at Georgia Gwinnett College.

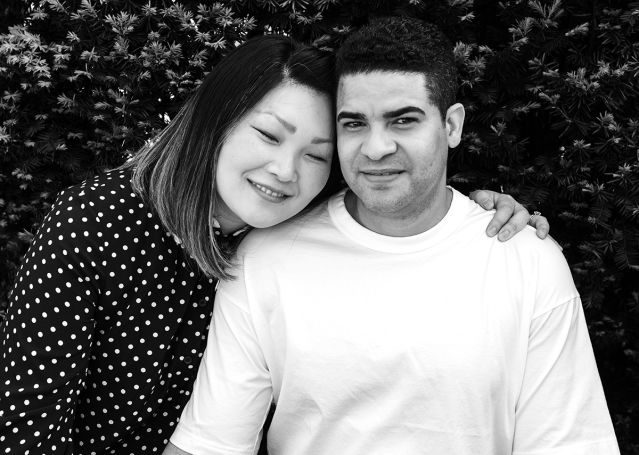

Julia Choi-Rodriguez & Roger Rodriguez

“My husband Roger tells me every morning when he wakes up, like a mantra, ‘Mujer [his nickname for me] is beautiful. Hombre [my nickname for him] loves Mujer.’ And then we squeeze in a good bear hug,” says Julia Choi-Rodriguez, of Montclair, NJ. “That lovey-dovey time makes us grateful for another day and for each other, before we get pulled into the million things we have to juggle. Without that feeling of connection, life could weigh on a relationship for sure. We have our fair share of off days, but we always come back to our mantra: 'Hombre loves Mujer.'"

Why We Still Love Partners Who Aren’t Ideal

When a partner’s sexual ideals are not met, it can have consequences for a relationship—unless the couple can foster a certain trait.

By Madeleine Fugère, Ph.D.

What traits would your ideal sexual partner possess? And once you had that partner, what types of sexual behavior would you find most satisfying? In a recent study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Rhonda Balzarini of Texas State University and colleagues investigated these “sexual ideals.” Realistically, many people’s actual sexual partners may not meet those high standards, so the researchers also explored the challenges unmet expectations present for long-term relationships and the qualities that could protect partners from the worst consequences of the disconnect.

The researchers conducted six studies involving primarily long-term, mixed-sex couples, most of whom identified as heterosexual and white. Across the studies, the team found that individuals who considered their needs unmet also felt less sexually satisfied and rated their relationships as lower in quality and commitment.

Since these findings are correlational—other factors could hamper relationship satisfaction, for example—the researchers also examined whether unmet sexual ideals can actually cause reduced relationship satisfaction. They asked some participants to recall two ways their partner responded to their sexual needs, some to recall 10 ways, and, in a control condition, asked others a question about their partner that was unrelated to sex. The team believed that recalling two instances would be relatively easy for participants, and thus that group might be more likely to feel that their sexual needs were met. Attempting to name 10 instances would be more difficult, making those partners more likely to feel their needs were unmet. After these and other manipulations, the team found that individuals who believed their partners were not meeting their sexual ideals felt reduced relationship quality, as compared to those who believed that their partners did meet their sexual ideals.

Working with Differences

These findings appear discouraging because it is easy to imagine that our partners and sexual experiences will inevitably fall short of our ideals. However, the researchers also identified a trait which, when possessed by either partner, can help ameliorate the negative effects. This quality is known as “sexual communal strength,” and for partners who are high in it, it can mitigate the effects of unmet ideals and help preserve relationship quality.

The researchers define sexual communal strength as the extent to which individuals are motivated to meet a partner’s sexual needs. When subjects had a partner who was higher in sexual communal strength, they did not report reduced satisfaction, commitment, or relationship quality—even if their sexual needs were not being fully met. Having a partner who expressed care and concern for their desires, the team found, protected relationships from the negative effects of unmet needs.

People who are highly responsive to a mate’s wishes, the findings suggest, may be better at navigating conflicts and may remain satisfied with their relationship, even when they have different interests or sacrifice their own preferences for a partner.

Interestingly, the team found that individuals who are very responsive to a partner’s needs also experience more sexual desire, enhanced relationship satisfaction, and commitment over time. People who are high in sexual communal strength may prioritize the benefits for their partner, leading them both to report greater satisfaction. Again, it is important to note that partners high in sexual communal strength may still believe that their sexual ideals are not being met; they are just better able to maintain satisfying relationships despite such feelings.

These studies suggest that your partner’s level of sexual communal strength may have a larger impact on your relationship satisfaction and commitment than your own level. The helpful effects of a partner’s sexual communal strength did not diminish even when researchers controlled for couples’ sexual frequency and levels of sexual desire.

The authors believe their study represents the first evidence that having a sexually communal partner might help people maintain sexual satisfaction over time even when they have unmet ideals. It’s also encouraging that our perception of our partners’ sexual communal strength can be enhanced just by remembering a few instances when they were attentive, responsive, and motivated to meet our sexual needs, which is why that could be a healthy and productive practice to adopt in a relationship.

Madeleine Fugère, Ph.D., is a professor of social psychology at Eastern Connecticut State University and the author of The Social Psychology of Attraction and Romantic Relationships.

Jim & Jill Pratzon

“Our relationship is an experiment in love, and we’re not done yet—never will be,” says Jim Pratzon of New York City. His wife of 30 years, Jill, advises other long-term partners that if they ever feel doubts, they should look back to look forward: “Look at those old photos of the two of you, when you were new to being in love. Look at the smile on your face. Look at how beautiful your partner was—and know that he or she is still that same person but even richer and more nuanced.” It’s an outlook that works for her: "When he plays me a song we used to dance to in the 80s, I'm his."

Submit your response to this story to letters@psychologytoday.com. If you would like us to consider your letter for publication, please include your name, city, and state. Letters may be edited for length and clarity.

Pick up a copy of Psychology Today on newsstands now or subscribe to read the rest of the latest issue.