The Man Who Wouldn't Lie

How Michael Leviton diverged from his family’s extreme view of dishonesty.

By Michael Leviton published January 5, 2021 - last reviewed on March 18, 2021

One playtime in kindergarten, I fell from a swing and collapsed in tears on the blacktop. A young woman who must have been a teaching assistant picked me up in her arms and lifted me onto her lap, stroking my head and cooing, “You’re so brave. You’re so brave.”

Because I hadn’t done anything brave that I could recognize, I suspected she might be lying. I asked her, in what I’m sure was a classic tearful kindergartner whine, “What did I do that was brave?” Ignoring me, she continued telling me I was brave. I’d already learned that this kind of avoidance—refusing to answer questions or justify oneself—was a sure sign of lying. “I didn’t do anything brave,” I told her. “You’re trying to trick me so I’ll stop crying!” She ignored me a second time, so I said, “Stop lying!” I continued calling her a liar until she fell quiet and stopped stroking my head.

In the car, going home from school, I told my mother my story about falling off the swing. “I was crying on the ground, and she said I was being brave.”

“Crying can be brave,” Mom said.

“If crying on the ground is brave, what isn’t brave?” I asked.

Mom thought for a second. “If you never rode a swing again,” she said. “That wouldn’t be brave.”

“But she didn’t know if I would ride a swing again!” I said.

Mom cracked up and beamed. “You’re right,” she told me. “Nothing gets by you, Michael!”

“Nothing gets by me!” I said proudly. My focus on making myself untrickable was troublesome enough but, even worse, I also refused to let anyone else be tricked.

The next time I caught this teaching assistant comforting another crying child, I walked over and said: “She knows you’re not brave. She’s just lying to trick you into feeling better!”

Of course, pretty much everyone insisted that what my family called “lying” wasn’t dishonesty at all, that we sounded absurd referring to perfectly normal behavior as fraud. The word lie meant something different to us, and it covered an overwhelming percentage of how others interacted. To us, people’s politeness was lying, their tact was pandering, their indirectness was cowardice, and their omission was manipulation. Even worse, lying didn’t have to be intentional. Self-delusion was dishonest too. We never ceased to be shocked by what we considered the most common type of dishonesty: a lack of interest in self-expression. We watched as everyone around us recited conversational lines we’d heard hundreds of times, talking only about what they were supposed to, as if performing a script without noticing. We couldn’t understand why anyone would prefer this to authenticity, let alone why this script would be so popular.

Mom had been raised to people-please, to sacrifice her authenticity for others’ comfort and measure her own value by whether she was liked. She didn’t want me to carry that same burden, so she pushed the idea that it wasn’t my responsibility to make everybody like me, that it mattered more if I liked myself. Others were in charge of their own feelings and if they didn’t like my truest self, they could just leave.

My father’s family, on the other hand, had been blunt, critical, and uncompromising for generations. But while they were happy to air their insulting opinions, they couldn’t handle criticism themselves. So, Dad was hung up on the idea that one had to feel comfortable both giving and receiving criticism, to long to hear others’ real thoughts and feelings, no matter how upsetting they might be.

My parents weren’t very organized about their philosophy. They had no official manifesto. But just by being themselves, they raised me as a correction to their families, and to our society. I was not supposed to fit in with the ridiculousness of our culture, but rather to resist it at every turn. And there was no better place to start my revolution than in kindergarten.

Afterschool conversations with my parents became a daily ritual. In the car, I’d excitedly list for Mom all the lies I’d caught.

Once I was supposed to deliver a speech at an assembly, but I didn’t want to memorize it. The teacher said I had to learn it by heart or she wouldn’t let me give the speech, so I told her, “OK, I don’t have to give the speech.” When I said that, she changed her tune and told me I didn’t have to memorize it.

“You called her bluff!” Mom said, finding me hilarious, as always.

At age 9 or 10, I came up with a lie test that proved useful in many situations. I’d ask myself two questions. First: Can I recognize what the person hopes to get out of this lie? Second: Is this what an uncreative person would make up to achieve that outcome? For example, if a child told me his Dad was a fighter pilot, I’d ask myself first whether I recognized his goal in saying this. Clearly, he wanted me to think his Dad was cool and that, therefore, he was cool. Then I’d ask myself if this was the type of lie an uncreative person would make up to achieve this gain. I decided, yes, that lying about one’s Dad having a cool job that was something famous that I’d seen on TV might impress me. And so I determined that his father probably wasn’t a pilot. If a kid, on the other hand, said his dad was an accountant, it was harder to determine what he would hope to gain from the statement if it was a lie. Further, it would have been a unique lie, one I’d never heard before. Most lies weren’t that creative. I would have determined that his father was likely an accountant.

I cared only about spotting the lie, not empathizing with the liar. For instance, it never would’ve occurred to me that the kid who lied about his father being a pilot might have no father, or have an abusive father, or have some other family trauma or shame that led him to lie to random people. I saw only the preposterousness of the lie. I could have used my talent for lie-spotting as a method of identifying suffering, seeing who needed compassion or help. But I’d missed that part of the equation. For me, these lies were just hilarious, and the liars, foolish and pathetic.

My lie-spotting became second-nature, as I internalized my lie tests and lists of classic cons. Lies stood out in red for me. I spent my teenage years and early adulthood calling people out and asking them to stop lying to me. But they refused, clinging to their claims that they’d been honest.

After decades of this, I’d had enough awkward conversations, been laughed out of enough job interviews, rejected by enough friends, denied enough apartments, and had enough romantic possibilities poisoned that I decided maybe everybody else knew something I didn’t. Maybe their insistence that they’d been honest wasn’t just another lie; maybe it was somehow genuine. I attempted a new kind of lie-spotting, directed this time at my own understanding of other people, at what I told myself.

Once I switched my honesty-obsessed brain to a different setting and took off my lie-colored glasses, it became clear that others weren’t trying to trick each other. What I called “dishonesty” was just how our culture agreed to communicate. The social script connected people, made them feel safe, understood, even loved. While I was calling out everything untrue, separating myself, others were echoing each other and learning a shared language. They cared about being kind, making friends, and feeling comforted—all things more important than the truth.

So, I’ve spent the last 10 years lying, at least according to my definition of the word. When someone seems to want to speak without hearing my opinion, I’ll imply that I agree. If someone angry or upset says something they don’t mean, I no longer point out that they probably don’t mean it.

Though I lie daily—and notice it every time I do—I’m still perceived as vastly more honest than most. But I find my tempered honesty is more appreciated. When invited to, I’ll tell personal stories and listen excitedly to others’ personal stories. I’ve never flinched at hearing other people’s feelings, and people can sense that. But I no longer force honesty on everyone indiscriminately.

My family understands my new relationship to honesty, though they’re not always willing to be dishonest this way themselves. My parents are still very authentic, but I notice small examples of their holding their tongue in ways they likely wouldn’t have before. Yet Mom still feels empowered by saying how she feels even if others won’t like it. And I think she still believes the truth will help, that it’s better for us all to truly know each other and be known by those we care about. I think many who grew up having to hide themselves feel similarly empowered; I can’t blame them. No matter how dishonest I may be in my regular life, it’s always freeing to spend time with my family and not need to lie at all. I’m still a sucker for those who love the unvarnished truth in all its hilarious, thrilling, heartbreaking glory.

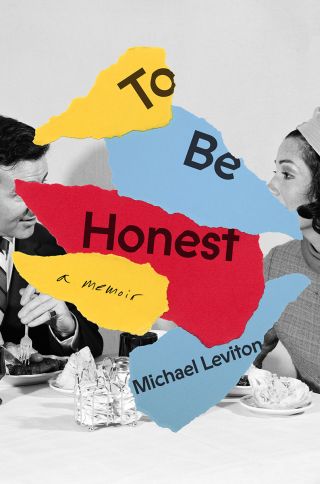

Michael Leviton is a writer, musician, and photographer. He is the author of To Be Honest: A Memoir.

Facebook image: New Africa/Shutterstock