How to Win an Election

The high-stakes science of campaign messaging reveals that success at the ballot box hinges more on how you feel about things than on what you think about them. Is anyone getting it right?

By Drew Westen Ph. D. published April 29, 2020 - last reviewed on May 26, 2020

Do you care about the unemployed, Medicaid recipients, and DREAMers? Whether you do or not, you’re likely going to be hearing a lot about them in the coming months, as America heads into a heated presidential election.

And if you do care, you should wipe every one of those phrases out of your vocabulary.

Why? Because it is hard enough to run against a tough opponent who does not share your values. You don’t also want to run against the human brain. It is a formidable adversary. And every one of those words and phrases is working for the neural opposition.

For more than two decades, I have been studying political decision-making and have made some counterintuitive discoveries about the mind of the voter. My first research, inspired by the impeachment of President Bill Clinton, showed that neither knowledge of the Constitution nor knowledge of what he had done predicted people’s “reasoned beliefs” about whether he committed high crimes and misdemeanors. But three things did—their feelings for their political party (partisanship), their feelings about the man himself, and to a much lesser extent, their feelings about feminism.

Later neuroimaging studies confirmed no signs of intelligent life when people were purportedly reasoning about unflattering information regarding a preferred political candidate. Neural circuits typically active in reasoning tasks never turned on. What did light up were circuits that traffic in negative emotions and Houdini-like efforts to escape—until they came up with a satisfying rationalization that eliminated the problem.

Then something totally unexpected happened. Their brains actually gave them a little emotional pat on the back for their efforts. There was a flurry of dopamine activity in reward circuits. I came to understand that it is hard to change the partisan brain because we get rewarded for lying to ourselves.

I have found that it is sometimes difficult for people to swallow the truth about reason. But it’s important for anyone who cares about the outcome of elections. It’s not that rational thinking is irrelevant when we pull that voting lever, but that we think for a reason, and the reasons are always emotional in nature. The only things we reason about are the things that we care about. Our feelings are our guide to action. Reason provides a map of where we want to go, but first we have to want to go there.

In politics as in the rest of life, we think because we feel.

Politics, then, is less a marketplace of ideas than a marketplace of emotions. To be successful, a candidate needs to reach voters in ways that penetrate the heart at least as much as the head. That makes political messaging critical—and perhaps about to determine the course of American history.

The Political Brain

In 2007, as a research and clinical psychologist who had watched one Democratic presidential candidate after another go down in flames, I researched and wrote a book titled The Political Brain. It dissected how candidates might talk with voters if they started with an understanding of the way our minds actually work.

As was readily apparent from their campaigns over decades, Democrats and Republicans have had two very different implicit visions of the mind of the voter. Republicans talked about their values, such as faith, family, and limited government. Their think tanks are feel tanks and fuel tanks, generating and testing what the brilliant wordsmith on the right, Frank Luntz, called “words that work.”

Democrats, in contrast, talked about their policy prescriptions, bewitched by the dictum that “a campaign is a debate on the issues.” Their think tanks brought in fellows to work out policies based on the best available science. Perhaps blinded by their indifference to emotion, they left to chance the selling of those policies to the public.

Armed with a vision of the mind in which good ideas, even when described to people in terms they might not understand or find emotionally compelling, would somehow sell themselves, Democrats consistently lost elections. At the time I wrote the book, only one Democrat, Bill Clinton, had been elected and re-elected to the presidency since FDR six decades earlier.

Survey data across decades of elections show that success or failure at the ballot box tends to reflect, first and foremost, voters’ feelings toward the parties, the candidates, and the economy, in that order. Then come feelings toward candidates’ specific attributes, such as competence or empathy. Feelings on any given issue come in a distant fifth in predicting election outcomes. Voters’ beliefs about the issues barely register. And except for political junkies, most voters are neither interested in detailed policy prescriptions nor competent to assess them.

What voters want to know are the answers to two questions: Does this person, and does this party, share my values? And do they understand and care about people like me? Those turn out to be pretty rational questions. No one can predict a black swan or coronavirus pandemic, but you’re likely to feel comfortable with the decisions of leaders who share your values and care about people like you.

The 2016 and 2020 elections continue a familiar pattern. No doubt sexism (and some help from Vladimir Putin) contributed to Hillary Clinton’s defeat and to the poor showing of Senator Elizabeth Warren in the Democratic primaries. But Warren’s fate was as predictable as Hillary’s, thanks to her Hillary-like message, “I have a plan for that!”

Funny, I don’t remember Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Plan” speech. But there are reasons rooted in human psychology and evolution that we all remember his dream.

Three Principles of Effective Messaging

In the nearly 15 years since writing The Political Brain, I’ve had the opportunity to interact with about 100,000 voters as a political message consultant, juggling academic work with developing and testing messages for political and other organizations, whether in focus groups, telephone surveys, or online dial-testing, in which voters move their cursor along a bar, rating their response as they listen to messages or ads. (Full disclosure: Although I work for organizations on the Left, this article is about the role of psychology in the science and practice of politics and is not written from a partisan perspective. If anything, my findings shine a harsh light on the Democrats.)

Online dial-test technology gives voters the opportunity to provide a second-by-second rating of how compelling they find what they are hearing or watching, which gives me the opportunity to see how voters respond to every word or phrase and how different groups of voters respond to the same message.

Studying voters’ responses over the last several years has allowed me to distill three basic principles central to effective political messaging, all rooted in the way our minds and brains work.

Principle #1:

Know what networks you’re activating. Our brains are vast networks of neurons, which combine in millions of ways into circuits that not only maintain our lives but create all of our thoughts, feelings, and actions. Of most significance to persuasive messaging are networks of associations, sets of thoughts, feelings, images, memories, and values that become interconnected over time. These networks are primarily unconscious, always whirring in the background, directing our thoughts, feelings, and behavior.

Nothing could be more important in political communication than knowing which neural wires we are inadvertently tripping, which networks we want to activate or connect, and which ones we want to deactivate.

Consider this phrase: the unemployed. What’s wrong with that? Just about everything, because it trips some inadvertent wires.

For starters, it takes real people with pain-lined faces and turns them into nameless, faceless abstractions. If you want people to feel something for the unemployed, you need to do just the opposite. It also turns a group of people that likely includes someone you know and care about yourself—and among whose ranks you have likely been at some point —into a them. And then there’s the just-world hypothesis—our tendency to rationalize away bad things that happen to good people. Speaking of the unemployed cries out for just-world sentiments such as, “I wonder what they did to lose their jobs?” or “Perhaps they are just lazy.”

All of this happens unconsciously and in the flicker of an instant, so that by the time you’ve gotten half a sentence out, you’ve already taken two steps backward, and none forward. The alternative is simple and humanizing, rather than abstract and dehumanizing: People who’ve lost their jobs. You can literally feel the difference from the unemployed. And to inoculate against the just-world hypothesis, try People who’ve lost their job through no fault of their own.

Abstractions activate a thin strip of cortex—the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex—that plays a central role in neural circuits involved in reasoning and conscious thought. But those aren’t the circuits that move levers in the voting booth.

If you care about policies that help people who are unemployed, then you want to evoke empathy for those people. The brain has circuits that evolved specifically to create empathy toward others. These neural circuits, the ventromedial and orbital areas of the prefrontal cortex, are also just a stone’s throw away from circuits involved in emotional processing. And our language captures something important about emotions: They move us.

How about Medicaid recipients? What image comes to mind when you think of a recipient? If you’re like most white people, it is outstretched hands, which are looking for a handout—a phrase that evolved from the gesture. Recipients are also passive. The term does not connote people actively seeking work or trying to help themselves. That is why referring to people on Medicaid is equally destructive: It suggests they are on the dole—back to outstretched hands.

Making matters worse, although the majority of people who rely on Medicaid for their health are white, the phrase tends to activate unconscious or implicit prejudice, as most white people who hear Medicaid recipient picture poor people of color, with all the conscious and unconscious bias it entails.

The alternative, once again, is to turn people into people: People who rely on Medicaid for their health care. They are not recipients. They are not on anything.

And there is a way to turn Medicaid recipient into something powerful. No anti-Medicaid message I have ever tested can block the 20-point boost in favorability delivered by a message that begins with these words: Chances are, if you have a parent or grandparent in a nursing home, Medicaid is paying for their care. People in nursing homes are often disabled—cognitively, physically, or both—but we love and care about them, either because they are our beloved relatives or someone else’s, and they deserve dignity in later life or care for their illness. And the hero of the story is Medicaid, which is actively and benevolently paying for their care.

There’s still room to up the ante and make the statement even stronger—10 favorability points stronger. Just precede it with one clause: Whether you’re white, black, or brown, chances are, if you have a parent or grandparent in a nursing home.… Why does that improve the message? First, it deactivates the implicit stereotype among white people of Medicaid recipients and the negative emotion activated by that stereotype. Second, the them becomes us. The phrasing is inclusive in a way that doesn’t feel like pandering or indulging in identity politics. It is about all of us, and it doesn’t matter what color we are.

Which brings us to DREAMers. Like the unemployed and Medicaid recipients, it’s an appeal to empathy without the appeal. And it adds an element of unintelligibility to the average voter. Why are they called DREAMers? What are they dreaming about? What’s the story with the capital DREAM? (It’s an acronym for a piece of legislation with a name no one knows.) And perhaps most important, why do the children of undocumented immigrants get to have the American Dream when, for the first time in history, three-quarters of Americans do not believe that their own children will be better off than their parents—the core of the American Dream?

So who are DREAMers? Try this: children who have never pledged allegiance to any flag other than ours.

Principle #2:

Speak to voters’ values and emotions. Our emotions and values are not arbitrary. We have them for a reason. Positive emotions draw us toward things, people, and ideas we believe are good for ourselves and the people we care about; negative emotions lead us to avoid or fight them. In politics, messages that tap into hope, satisfaction, pride, and enthusiasm, on the one hand, and fear, anxiety, anger, and disgust on the other, move people, first of all to vote, then to vote for one party or candidate versus another.

What all human beings find compelling is rooted in the structure and evolution of our brains, and it is expressed in our values as well as in our emotions. Family is a value that matters to people across the political spectrum. Natural selection, at its core, is about survival, reproduction, and alliances with people who help us survive, reproduce, and care for our kin.

For years, the political left ceded family values to the right, which tested that term 40 years ago, saw a winner, and spent hundreds of millions of dollars branding it as theirs. For more than a generation, that effort essentially tied the hands of Democrats in speaking about perhaps the most important value to our species and the source of the most powerful of emotions.

Principle #3:

Tell a coherent, memorable story. Our brains are wired to understand, to be drawn to and into, and to remember and pass along to others information presented in a particular form: narrative. As a species, we survived for about 200,000 years before the emergence of literacy, requiring some mechanism for transmitting knowledge and values across generations. All known human societies have myths and legends in the form of stories..

Issues are not narratives. Nor are 10-point plans. Narratives have protagonists and antagonists. At least in the West, narratives tend to have a particular story structure, or grammar, recognizable even to preschool children. It includes, among other elements, an initial situation, a problem, a battle to be fought or hill to be climbed, and a resolution. Stories also tend to have a moral. The particular values embedded in that moral are central to the difference between the right and the left.

Perhaps the most important lesson I have learned from testing hundreds of thousands of narratives on the most important issues of our time, from contraception and abortion to climate change and economics, is that virtually every successful political narrative has a structure derivative of this grammar. Except for attack ads, which diverge only partly from this structure, effective messages begin with a statement of values that transcends political divides (to establish a connection between speaker and listener), then raise concerns in vivid ways that activate emotions, particularly moral emotions, such as fairness or indignation. Finally, after briefly describing a solution, but skipping details, they end with a sense of hope.

A Family Doctor for Every Family

In 2020, high-quality affordable healthcare for all Americans is one of the top priorities for voters, as it has been for three decades. Illness doesn’t come in red or blue. Lack of insurance harms people on both sides of the aisle.

When Barack Obama first ran for president 12 years ago, several organizations that had been working on the issue hired me to develop pro-reform messages and test them against potential attacks. Public support for expanding healthcare coverage proved so widespread that the issue was bulletproof—but only with effective messaging. If any of the messages began with, I believe in universal healthcare, the percentage who supported reform roughly equaled the percentage opposing it, given a tough narrative from the right about “socialized medicine” or “a government bureaucrat between you and your doctor.” But if the same message began with, I believe in a doctor for every family, support exceeded opposition 70 percent to 30 percent.

Universal healthcare is abstract, cold, and sterile—just like the name of the bill that succeeded in at least partly expanding coverage, the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The name does not capture many of the most important values that move voters on healthcare: the choice to retain the close personal connection they may already have with their doctor and the ability to choose a plan they believe is best for their family.

Universal healthcare also unconsciously activates neural networks that evoke both prejudice and legitimate concerns about quality, as white voters picture images of clinics with long lines, packed with people of color getting the kind of inferior care many people of color currently receive. Had the bill instead been named A Family Doctor for Every Family—parallel to George W. Bush’s signature legislation on education, No Child Left Behind—it would have activated entirely different neural networks, connoting a personal connection with their doctor, high-quality care they have chosen, and coverage for everyone.

Within the first hundred days of the Obama administration, the House of Representatives passed a healthcare bill that captured what the American public wanted. The Democrats said it was about making sure everyone has good, affordable care. It took the Senate over a year to pass a watered-down version that dropped key provisions—a Medicare-like option to compete with private insurance and the power of the government to negotiate drug prices. By the time the bill passed, the Republicans had captured the narrative, turning a once-popular reform bill into “socialized medicine.”

Since then, Republicans have pushed to curtail the law and refused to amend it in ways that could improve care for millions more people. The ACA covers 20 million people who didn’t have coverage before, including all children, and permits coverage of people with pre-existing conditions. But it’s still possible to get stuck with a $10,000 deductible, and medical expenses remain the leading cause of bankruptcy.

Republican opposition to the Affordable Care Act, deficient as it is, cost it control of the House in the 2018 midterm election. The Democrats enter the 2020 race with the challenge of selling to voters a broken program and the promise of fixing it.

To start with, what do they even call it? Most voters do not know what the Affordable Care Act is. Many speak negatively about Obamacare, not realizing they use and like it. Research shows that the two worst things to call either extending the ACA or taking a different path to healthcare are the names Democrats are currently using: Obamacare and Medicare for All. It was Republicans who coined the name Obamacare in an attempt to kill it. Any program named after a president will have the lasting enmity of the voters of the other party.

Medicare for All, although assuring that everyone would be covered, scares tens of millions of voters who fear it would create lowest-common-denominator care. A defining feature of U.S. culture is individualism; for all does not resonate with the political center.

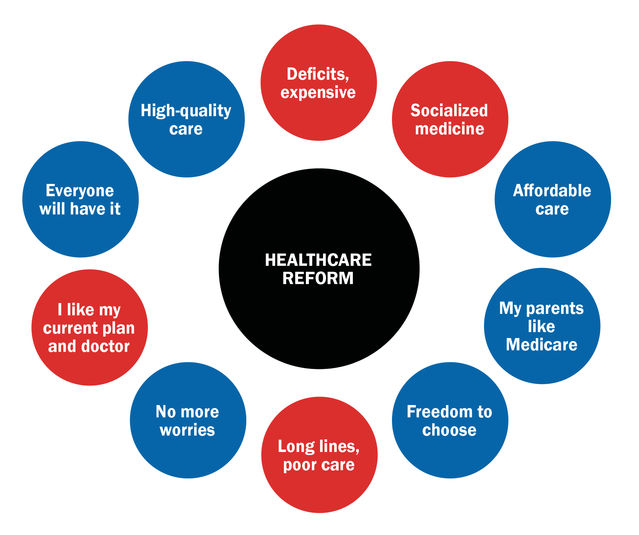

Given that roughly 40 percent of voters support or oppose any given policy from the start because of their partisan affiliation, the associative networks of swing voters are instructive (see the diagram on page 69).

Voters want a solution to healthcare issues that addresses their values, interests, and concerns. They want high-quality, affordable care, with freedom to choose among plans, freedom from worries about problems like pre-existing conditions, and coverage for everyone. At the same time, they do not want to lose their current plan or doctor, they worry about any program that will create long lines and poor-quality care, and they worry about the cost of the program. Many swing voters are also leery of “socialized medicine.”

The evidence points to fixing the program begun by Obama. How to talk about it? Incorporating the principles of messaging, a winning campaign might sound like this:

It’s time to finish the job we started on healthcare, not tear it down. Democrats built a high, rock-solid floor on what insurance companies had to cover in every plan on the market, including pre-existing conditions, procedures your doctor orders, and life-saving preventive medicine, like breast cancer screening. Since the healthcare industry couldn’t lower the floor, they sent premiums, deductibles, and copays through the roof. So now it’s time to build the ceiling. That means limiting the amount insurance companies can raise fees every year. It means letting the most powerful union in the world that is supposed to represent the interests of working people—the United States government—negotiate drug prices with the pharmaceutical industry, or we’ll buy our drugs where they’re less expensive. And it means giving insurance companies some healthy competition by letting people of any age choose Medicare if they prefer it. Let’s finish the job so no Americans will ever again have to choose between taking their child to the doctor and putting food on the table for their family.

That would leave only the question of what to call it. Democrats might do well with “A Family Doctor for Every Family.” That’s a clinic Americans would be happy to visit.

What People Think

Networks of associations are always active.

Because so much is at stake in political messages, it’s important for candidates to capitalize on the associative power of words and phrases. Here is a glimpse into the minds of people when they hear the words healthcare reform.

Submit your response to this story to letters@psychologytoday.com. If you would like us to consider your letter for publication, please include your name, city, and state. Letters may be edited for length and clarity.

Pick up a copy of Psychology Today on newsstands now or subscribe to read the rest of the latest issue.

Facebook image: Sean Locke Photography/Shutterstock