Inner Dinner

Prebiotics get delayed treatment in the gut, and that's good news for the brain.

By Annie McDonough published September 4, 2018 - last reviewed on November 5, 2018

Once upon a time, gut mechanics were simple. You sat at a table, ate your dinner, a bunch of enzymes along the gastrointestinal tract released the nutrients, and the bloodstream delivered them to all points to keep your body going. But the discovery that the gut hosts billions of bacteria that are metabolically enterprising has changed all that.

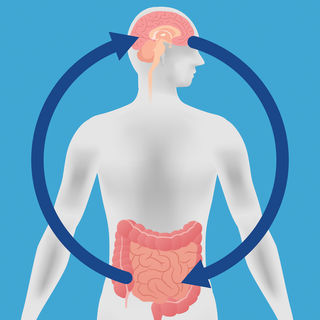

Scientists are still figuring out how the food we eat is fully processed, but they do now know that how nutrients nourish you is just the half of it. What you eat doesn't feed you alone; it supports the two pounds of bacteria and other microorganisms—the microbiome—that make their home in your gut lining and, in ways still being discovered, profoundly influence your mental and physical health.

Here's the funny part: It's what your body can't digest that may be the biggest boon to your well-being. A thriving secondary market for indigestibles exists in the colon, the end of the digestive line. Diverse families of bacteria permanently stationed there selectively feed on incoming supplies of enzyme-resistant carbohydrates (generally by fermenting them) and consequently flourish, determining the very makeup of the microbiome. The composition of the human microbiome, researchers are finding, influences such functions as sleep, memory, appetite regulation, vulnerability to stress, susceptibility to anxiety and depression, and more.

Collectively, the resistant starches are known as prebiotics because they serve as supper for the colon's colonies of bugs. Under normal conditions, the microbes in your intestinal tract are a diversified lot; prebiotics, whether consumed naturally in foods or taken as supplements, are critical to maintaining a rich array of bacteria.

"Research is emerging to suggest that prebiotics may influence stress-related behaviors and mood," says Jane Foster, an associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience at Canada's McMaster University. Notably, prebiotics influence the production of gut bug-derived metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids, compounds that play a pivotal role in gut-brain communication.

Studies show that prebiotics curb the neuroendocrine response to stress, dampening secretion of the hormone cortisol. They also modulate the way the brain processes emotional information, keeping it from dwelling on negative stimuli.

The best-known and -researched prebiotics are the complex carbohydrates FOS (fructooligosaccharides, found in fruits and vegetables) and GOS (galactooligosaccharides, found in legumes). But there's new evidence that polyphenol antioxidants in green tea, red wine, blueberries, and cocoa boost populations of beneficial bacteria in the microbiome.

Inulin, a prebiotic found in chicory, has been shown to help normalize weight in overweight or obese adolescents. When researchers supplied 38 children with either inulin or a placebo, those in the inulin group not only experienced normalized weight gain for their age, but the prebiotic also reduced whole body fat and trunk fat. It also improved the diversity of gut bacteria. The researchers believe that the use of prebiotics can be an easy and effective way to help adolescents control weight.

Adolescence may be a particularly important time for regulation of gut health because the diversity of the microbiome during that period can have lasting effects. Research indicates that the gut biome helps set the body's stress threshold for life during certain sensitive periods of development, when the brain is growing especially rapidly. The period just after birth is one such time; adolescence is another.

The effects of prebiotic consumption may be different at different stages of development, says Foster. But overall, she observes, prebiotics are dietary components that can promote gut health with links to well-being at any age.

Prebiotics and Their Sources

Prebiotic: Fructans (fructooligosaccharides

and inulin)

Food Source: Asparagus, sugar beets, garlic, chicory, onions, Jerusalem artichokes, wheat, honey, bananas, barley, tomatoes, rye

Prebiotic: Galactans (galactooligosaccharides)

Food Source: Human milk, cow's milk, legumes

Prebiotic: Xylooligosaccharides

Food Source: Bamboo shoots, fruits, vegetables, milk, honey, wheat bran

Fiber Optics

Prebiotics were first defined in 1995 as "nondigestible food ingredients that beneficially affect the host by selectively stimulating the growth and/or activity of one or a limited number of bacteria already resident in the gut."

- Largely nondigestible carbohydrates (fiber), prebiotics act as fertilizer for specific strains of healthy gut bacteria.

- The most common prebiotics, FOS and GOS, primarily promote the growth of bifidobacteria in the gut.

- Every person's microbial profile is distinct, influenced by genetics, age, and sex as well as diet.

- Foods particularly rich in prebiotics include chicory root, Jerusalem artichokes, raw garlic, leeks, and onions.

- While the RDA for fiber is 25 to 38 grams a day, Americans on average fall significantly short of that amount, consuming only about 16 g/day.

- When combined with milk proteins, prebiotics consumed in early life have been shown to temper the negative impact of stress on sleep.

- Prebiotics can normalize weight gain in overweight and obese children.

- Dietary prebiotics have been shown to reduce depression and anxiety-like symptoms in adult mice in preclinical trials.

- Prebiotics can reduce inflammation and inhibit pathogens.